In late October, with a Halloween moon appearing in the night sky, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) adopted a controversial notice of proposed rulemaking on “geomagnetic disturbances,” with comments due Christmas Eve. Unlike most FERC actions, aimed at terrestrial concerns, this rule would order the North American Electric Reliability Corp. (NERC) to set in place a two-stage program aimed at protecting the U.S. transmission and distribution network from damage caused by large-scale coronal mass ejections, often referred to as “solar storms.”

“Grid bonkers,” is how one veteran industry observer describes much of the recent activity at FERC and its quasi-public satellite NERC. Earlier in the fall, NERC issued the third and likely final draft of its fifth generation of “critical infrastructure protection standards,” a.k.a. CIPS 5. It would move the nation’s electric utilities from a cookbook, checklist approach to protecting plants and networks from cyber threats to a systems-oriented regime.

As the import of CIPS 5 was seeping into industry consciousness, FERC in late September established a new office dedicated to cybersecurity. The agency created the Office of Energy Infrastructure Security to “leverage its existing resources with those of other government agencies and private industry in a coordinated, focused manner,” in the words of FERC chairman Jon Wellinghoff. The new office is headed by Joseph McClelland, who ran FERC’s Office of Electric Reliability since its creation in 2006 in the aftermath of the 2005 Energy Policy Act, upgrading FERC’s authority over the grid. Michael Bardee, FERC’s general counsel, replaces McClelland at the reliability office, where he will spearhead the solar storm rule.

At the same time, the industry is twisting and turning over how to implement, or respond in court to, FERC’s Order 1000, issued in August 2011, which sets in place a new regime for regional planning of transmission, along with the red-hot issue of who pays for the benefits of a more robust and integrated grid. At FERC’s October meeting, where it proposed the new rules for solar storm protection, the commission also rejected a request for a rehearing on the rule from the Southwest Power Pool.

At a NERC webinar on cybersecurity in September, NERC chief Gerry Cauley described CIPS 5 as “the single most important set of standards we will produce this year.” In the coming year, NERC’s standard-setting agenda may be dominated by solar power: not the photovoltaic kind but rather the power of electromagnetic radiation from the sun to take down the electricity grid.

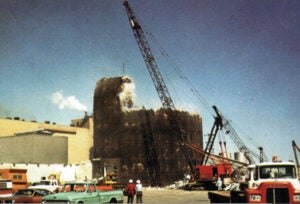

The industry has long known that solar storms, while low-probability events, can have a very high impact on electric system, blacking out large sections of the population for long periods, causing extensive and expensive damage to switchgear and transformers. Solar storms are not events that humans can prevent, so the fundamental challenge is how to prevent or minimize their damage.

Solar storms, says FERC in its October 18 proposed rule [Docket No. RM12-22-000], illuminate a gap in the existing reliability standards. While NERC has sought to downplay the impact of an electromagnetic assault from the sun, claiming that it will not cause catastrophic damage (also perhaps fearing the additional workload brought on by a new round of standard setting), FERC brushes this cavil aside. The commission writes, “our proposed action is warranted by even the lesser consequence of a projected widespread blackout without long-term, significant damage to the Bulk-Power System.”

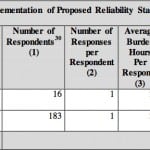

So in the proposed rule, FERC is setting a process in motion that will take at least the better part of 2013 to build just a foundation. Comments—and there likely will be plenty—are due at the end of the year (December 24) and new rules will start to take effect 90 days after FERC adopts a final rule. That will only be the start.

FERC’s proposed rule—a set of orders to its satellite NERC to impose on electric utilities—has two stages. The first, which the agency says should go into effect after that 90-day gestation, is “operational,” aimed at steps that would mitigate damage in the interim while utilities develop stronger measures to prevent damage. “While this deadline is aggressive,” says the notice, “mandatory and enforceable Reliability Standards requiring owners and operators to implement operational procedures should be established quickly to afford some level of uniform protection to the Bulk-Power System against” solar storms. Examples of these operational measures, according to FERC, include “reduction of equipment loading (e.g., by starting off-line generation), unloading the reactive load of operating generation, reductions of system voltage, and system and/or equipment isolation through reconfiguration of the transmission system.”

But operational steps are not sufficient, given the magnitude of the threat, says FERC. Over the succeeding six months, NERC must develop standards so that utilities can set up company-specific plans for coping with solar storms operational procedures should be established quickly to afford some level of uniform protection to the Bulk. These plans should be “based on factors such as the age, condition, technical specifications, or location of specific equipment. These strategies could include automatically blocking geomagnetically induced currents from entering the Bulk-Power System, instituting specification requirements for new equipment, inventory management and isolating certain equipment that is not cost effective to retrofit.”

What will be the price tag for protecting the grid against solar attack? Clearly, nobody knows the precise answer to that question. But FERC has some estimates that suggest these won’t be cheap fixes. The proposed rule notes that estimates for the cost of adding equipment to block rogue currents from attacking grounded transformers will run in the range of $100,000 to $500,000 per transformer. New large power transformers can run to $10 million a pop, and there are supply chain constraints. A recent Department of Energy report found that transformer supply is “a potential issue for critical infrastructure resilience in the United States….”

On the other hand, says FERC, conventional blackouts are very expensive, with estimates of the cost of the August 2003 four-day blackout (which led directly to the 2005 law that turned NERC from an industry voluntary group to a quasi-government institution) running from $4 billion to $10 billion, “with the Department of Energy calculating the total cost to be $6 billion.” A catastrophic solar storm could increase those figures substantially.

In a written statement accompanying the proposal, FERC commissioner Cheryl LaFleur, a former National Grid executive, said that while “the threat of geomagnetic disturbances damaging the power grid sounds like science fiction, [it] is in fact based on scientific fact. However, while the fact that geomagnetic disturbances can cause substantial harm to the electric grid is undisputed, the way in which that harm would occur is not without controversy.” She said the timing of rules to deal with magnetic storms is apt “because the US is facing considerable investment in our transmission grid, driven by a change in power supply and replacement of aging infrastructure. We have a big opportunity to make sure the next generation of transmission equipment is built to withstand geomagnetic disturbances.”

Running concurrently with the solar proposal is a proceeding in which NERC is defining “bulk electric system,” which has implications for the reach of the GMD rulemaking. Typically, Congress gave FERC jurisdiction over the bulk electric system, but didn’t define it. FERC and NERC have been wrangling over the definition ever since. In his recent House committee testimony, McClelland said that NERC’s description of the term results in “inconsistencies across regions” and “ambiguities.” In November 2010, the commission told NERC (Order 743) to come up with a definition consistent with FERC’s “bright line” of 100 kV and above being in FERC’s gambit. NERC says it plans to have work completed on this project by the end of next year.

Despite the aggressive schedule in the proposed solar storm rule, there is general understanding at FERC that the rulemaking and the subsequent implementation will be a long-term affair. The proposed rule states, “While the Commission proposes to direct the ERO to submit the proposed second stage Reliability Standards within six months of the effective date of a final rule in this proceeding, the Commission seeks comment on the feasibility of a six-month deadline.”

In September testimony to the House Homeland Security Committee, McClelland noted that under the law that gives FERC authority over the grid (new Section 215 of the Federal Power Act, created in the 2005 Energy Policy Act), the actual work of developing reliability standards falls to the “electric reliability organization,” or NERC, which must use “an open, inclusive, and public process. The commission can direct NERC to develop a reliability standard to address a particular reliability matter. However, the NERC process typically requires years to develop standards for the commission’s review.”

—Kennedy Maize is MANAGING POWER’s executive editor

FERC Proposes Regulatory Regime for Solar Storms

SHARE: