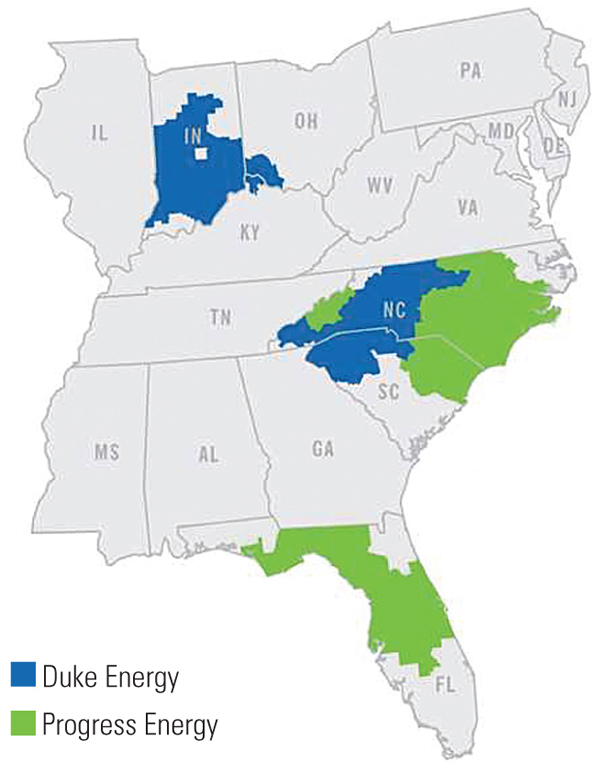

Duke Energy, the largest electric utility in the U.S. in terms of market value, is transitioning its generating fleet away from volatile and sometimes unprofitable wholesale markets and toward the traditional, regulated, cost-of-service model that prevails in much of the Carolinas and Florida service territories where Duke dominates.

Late last March, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) in Washington gave final approval for Duke Energy’s sale of 6.1 GW of generating capacity in Ohio, Illinois, and Pennsylvania (11 plants, six fueled by coal and five by natural gas) to non-utility generator Dynegy, recently emerged from bankruptcy. The deal was for $2.8 billion in cash.

The sale of the North Carolina–based utility giant’s merchant plants, which bid power into the PJM Interconnection and Midcontinent Independent System Operator’s (MISO’s) wholesale, merchant competitive markets, marked a major retreat for Duke’s role in wholesale competition. Now, Charlotte, N.C.–based Duke is concentrating its generating future in traditional, cost-of-service, state-regulated economic environments.

Return to Tradition

At the announcement of the plants’ sale to Dynegy in August 2014, Duke’s Marc Manly, head of the company’s commercial business operations, said, “This transaction is an important milestone in our strategy to exit the merchant generation business.” Duke CEO Lynn Good said earlier, “Our merchant power plants have delivered volatile returns in the challenging competitive market in the Midwest. This earning profile is not a strategic fit for Duke Energy and we have begun a process to exit the business.”

Evidence suggests that Duke was so intent on exiting competitive wholesale markets that it offered its merchant generating plants at a bargain-basement price. The investment website 24/7 Wall Street commented when Duke announced the sale of its merchant generation, “Dynegy seems to have come out on top in the deal.” When FERC approved the sale last March, Dynegy’s stock price jumped almost 10%. The ElectricityPolicy.com website (for which I also write) commented on the stock price rise: “It was an astounding move for an industry where precipitous drops or Olympian ascents in price are rare indeed.”

At the same time, Duke is moving to solidify its position in its traditional, regulated markets in the Carolinas and Florida. In early April, North Carolina Governor Pat McCrory (R), a former 29-year Duke employee, signed a bill that will streamline Duke’s purchase of the shares of the North Carolina Eastern Municipal Power Agency’s (NCEMPA’s) generating plants that Duke does not already own. The deal relieves a burdensome debt load facing the municipal joint action agency while increasing Duke’s generation under state regulation. An SNL Energy newsletter commented that the legislation McCrory signed “is seen as a crucial part of Duke Energy Corp. utility’s plans to take on 100% ownership of the NCEMPA assets and effectively reduce the power agency’s $1.9 billion in debt by more than 70%. NCEMPA for years has been looking for ways to pare down the debt incurred from its stake in generation development.”

Under the deal with the muni system, Duke will pay $1.2 billion to buy out NCEMPA’s interests in the 1,928-MW Brunswick Nuclear Plant, the 973-MW Shearon Harris Nuclear Power Plant, the 746-MW Mayo coal-fired plant, and the 2,457-MW coal-fired Roxboro plant. Duke will supply the municipal system with power under a 30-year wholesale power supply contract. The buyout amounts to about 700 MW of generating capacity. NCEMPA consists of 32 cities and towns that own distribution systems in the Tar Heel State.

The Path to First Place

Duke Energy has become, through mergers and acquisitions over several decades, the largest energy utility in the country in terms of market capitalization, most recently valued at some $57 billion. The company had 2014 revenues of $30 billion and total assets valued at $121 billion. The company has 57.5 GW of generating capacity (49.6 GW in regulated markets).

Duke Energy’s current business profile is largely the product of its aggressive former CEO, Jim Rogers. The charismatic Rogers, a former newspaper reporter and lawyer who was once a key employee of the now-disgraced Enron Corp. when it was just a conventional interstate gas pipeline, became head of Public Service Co. of Indiana in the early 1990s. He used that company to acquire Cincinnati Gas and Electric in 1994, creating Cinergy. Then Rogers wrangled a merger with the larger Duke Power Co. of Charlotte, N.C., a nuclear-heavy utility long under the reins of the legendary executive Bill Lee, a nuclear power pioneer.

Rogers emerged as CEO of the merged company in 2006 and soon set his sights on another North Carolina electric utility, Progress Energy, based in Raleigh, N.C., with significant operations in the Carolinas and Florida. Progress Energy was the product of a 2000 merger of Carolina Power & Light and Florida Power Corp. In 2011, Duke and Progress merged to create the current behemoth, Duke Energy.

The merger created bad blood between two executive suites. Under the terms of the deal, Progress CEO Bill Johnson was slated to become the head of the new company. But Rogers, for reasons still unknown, quickly lost confidence in Johnson and defenestrated him from the Duke executive suite. Johnson is now the head of the Tennessee Valley Authority.

Rogers retired in 2013 and was replaced by Good, a Rogers protégé with a background in financial management. An accountant by training, she served as Cinergy’s, and then Duke’s, chief financial officer. According to Duke’s website, Good “led the financial function, which includes the controller’s office, treasury, tax, risk management and insurance, as well as corporate strategy and development. In addition, Good was responsible for the information technology and supply chain functions.”

Good has had a rocky tenure so far, as the giant utility has faced large environmental and legal challenges related to coal ash storage pond leaks at some of its coal-fired power plants. A major spill into the Dan River in early 2014 highlighted the problem. Duke later admitted to leakages into surface waters from 14 coal plants, although the company says it isn’t sure they are all from coal ash ponds.

At the end of March, federal prosecutors filed multiple criminal charges against Duke for the coal ash pond leaks. The nine misdemeanor counts, the Associated Press reported, cover leaks at five plants. Duke said it has already negotiated a plea bargain that will let the company pay $102 million in fines. It has set aside the money to cover the penalties. Good will take a $600,000 hit on her annual paycheck. That’s a pinprick against her annual compensation package of $8.3 million, according to the Charlotte Business Journal. (Duke did not respond to multiple requests for comment for this article.)

North Carolina has also assessed Duke a $25 million fine for its coal ash handling practices at the company’s Sutton plant near Wilmington, N.C., the largest fine the state’s environmental regulators have ever levied.

Coal Proves Challenging

Duke, along with other generating utilities, is moving away from coal and toward gas in its regulated service territory—and not just because of coal ash issues. CEO Good commented in the company’s 2014 annual report, “Duke Energy has five new, cleaner-burning natural gas–fired power plants in North Carolina, replacing seven coal plants. This helps us meet new environmental standards and produce power more efficiently.”

Since 2011, says Duke, the company has closed 10 coal-fired generating plants, including seven of 14 in North Carolina (Figure 1). Says Duke’s Danny Wimberly, in charge of closing the utility’s old and outdated coal-fired units, “This is an important step for the company as it shifts to more modern technology, but at the same time, it’s bittersweet to see the smokestacks and buildings of our legacy plants come crashing down.”

|

| 1. In the beginning. Duke Energy’s coal-fired Buck Steam Station in Rowan County, North Carolina, shown here in a 1927 photo, was retired in 2013. Courtesy: Duke Energy |

Duke is also struggling with its 618-MW Edwardsport integrated coal gasification, combined cycle (IGCC) generating plant in Indiana (Figure 2). Duke Energy has long touted the IGCC plant as the future of coal-fired generation. Many in the electric utility industry have been boosting coal gasification and combined cycle generation for at least three decades, with little to show for the hyperbole.

Edwardsport, which went into service in mid-2013, has had serious teething problems, as POWER noted in a July 2014 article, “Does IGCC Have a Future?” As that article noted, “It reached 60% capacity in August, only to suffer mechanical failures this past winter that reduced output to a trickle in January and February.” The project also experienced tumultuous cost overruns, which totaled $1.5 billion when the plant went online.

Indiana regulators now face the issue of whether to allow Duke to recover the costs of Edwardsport from the state’s electricity customers. A coalition of environmental and consumer advocacy groups in Indiana is challenging Duke at the Indiana Regulatory Utility Commission, which began hearing the case in early February. They argue that “over the period from June 2013 to March 2014, the plant’s costs were 876% higher than if the power had been purchased on the market. Duke Indiana operates in the MISO marketplace where the cost of market purchases over the same period was $33.5 per MWh while Edwardsport came in at a whopping $327.03/MWh.”

Tough Love for Nuclear Plants

Duke has also experienced some nuclear wobbles in the past couple of years, mostly because of steps Progress Energy took before Duke acquired the rival utility in 2011. In 2009, Progress discovered significant structural problems with the containment at the Crystal River plant (Figure 3), which went into service in 1977. After years of study and discovery of additional problems, in early 2013, Duke announced it would retire the 860-MW plant on the Florida Gulf Coast near Tampa and decommission the Babcock & Wilcox pressurized water reactor. The site also houses four large coal-fired units.

|

| 3. Deemed not worth saving. Multiple problems at the Crystal River nuclear plant led to its closure in 2009 and retirement in 2013. Courtesy: Duke Energy |

Duke is asking Florida legislators for permission to borrow $1.4 billion to pay off Crystal River’s poor performance. The unit cost $447 million to build, but Duke says it still hasn’t finished paying off the construction of the plant and its operations through 2009.

Six months after the decision to close Crystal River, Duke pulled the plug on Progress’s planned Levy County nuclear station, designed at the height of the failed “nuclear renaissance.” The plant would have housed two 1,000-MW Westinghouse AP1000 advanced pressurized water reactors.

The Levy County site is close to Crystal River. Progress figured it could save costs by sharing facilities with the other nuclear plant. In 2006, the Florida Legislature passed a state law allowing the utility to recover the costs of the new plant in advance of construction at Levy County.

The nuclear renaissance proved stillborn as cheap natural gas soon dominated the economic environment for new generation. Progress delayed the Levy County plant, Duke bought Progress, and Levy County entered the long U.S. list of nuclear plants planned but not delivered. As part of the settlement with the state of Florida over the Levy County project, Duke was able to avoid public hearings on how the company allegedly botched the Crystal River repair program, according to the Tampa Bay Times.

Ivan Penn, the energy reporter for the Tampa Bay Times, wrote, “Further, the settlement guarantees Duke a minimum profit margin of 9.5% through 2018. As for Duke’s customers, the settlement stems the financial bleeding from the Levy and Crystal River misadventures at up to $3.2 billion.”

In 2007, at the height of the nuclear renaissance hyperbole, Duke asked the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) to approve a combined construction and operating license for a two-unit, AP1000 nuclear plant, the William States Lee III station, to be built in South Carolina at an estimated cost of $11 billion. That project has been treading water as the economics for nuclear have eroded. The company continues to carry information about it on the corporate website (and also displays information on the mothballed Levy County project).

Duke has avoided getting specific about the timeline for the Lee plant, saying it won’t get into details until the license application at the NRC has been approved. That could come in 2016. Among those following nuclear closely, the betting is that the Lee plant won’t move forward.

Looking Ahead

Looking to the future, Duke Energy is moving to add significant utility-scale solar in Florida, with some 500 MW of generation by 2024, although that’s a tiny increment to its existing nonrenewable generation of 57.5 GW. The company filed its “Ten-Year Site Plan” with the Florida Public Service Commission in April. The utility said its first solar site, with up to 50 MW of capacity, would see construction start this year, and another 35 MW completed by 2018. Duke said it plans to “retire half of its Florida coal-fired fleet” by 2018 as it brings on the planned solar generation. The company has also filed a plan with North Carolina regulators for an 80-MW solar project, which could be developed by the end of the year.

Duke’s shift away from competitive wholesale generating markets is part of a trend among utilities in a position to abandon wholesale competition for state regulation. Both American Electric Power (see the February 2015 issue of POWER) and Duke (see the Apr. 8 news story “Ohio Nixes Duke Energy Proposal to Guarantee Income from Coal Plants” at powermag.com) earlier this year failed in petitions to the Public Utilities Commission of Ohio (PUCO) to move shares of their merchant generation in the Buckeye State into state regulation. A similar case from Akron-based FirstEnergy is pending at PUCO, with hearings scheduled this month, according to Midwest Energy News (see sidebar) .

| Filling the Gap with GasThe retreats by Duke Energy, American Electric Power, FirstEnergy, and others in the Midwest wholesale markets have created major opportunities for non-utility generators to replace generation (often coal-fired) from the retreating incumbents with natural gas flowing from nearby fields opened up by hydraulic fracturing.

ElectricityPolicy.com reported recently on a spate of new non-utility gas-fired capacity announced in Ohio to bid into the PJM Interconnection in the face of major coal retirements, including:

■ The Swiss company Advanced Power’s 750-MW project in Carroll County, Ohio. ■ The 799-MW Oregon (Ohio) project, a venture of Energy Investors Funds (EIF) and I Squared Capital. ■ NTE Energy’s 525-MW gas-fired power plant in Middletown, Ohio, in Butler County. ■ Clean Energy Future-Lordstown LLC is proposing to build an 800-MW gas-fired plant in Trumbull County, Ohio. ■ NRG Energy’s conversion of the iconic 725-MW coal-fired Avon Lake power plant on Lake Erie to gas, waiting for state approval to build a 20-mile gas line from Dominion East Ohio and Columbia Gas of Ohio lines to the plant. Avon Lake has figured prominently over the years in discussions about reductions on coal-fired plant conventional emissions. |

Does Duke’s retreat to the traditional cost-of-service regulation business model represent a path to the future for electricity generation and distribution, or a shrinking away from a modernized, competitive business model that now covers more than half of the U.S.? The path Duke Energy follows in the years ahead, and where it ends up, may help answer that question. ■

—Kennedy Maize is an energy journalist and frequent contributor to POWER.