Work Process Optimization: Meeting the Challenge of Change

The competitive push for more efficient power generation prompted the management of East Kentucky Power Cooperative’s Spurlock Station to provide training and to implement standardized work processes in order to achieve higher productivity. To that end, Spurlock’s management collaborated with salaried and hourly personnel to design and implement work process optimization. Two years later, their proactive, operations-driven culture is promoting continuous improvement at this facility.

For more than 20 years, a two-unit coal-fired plant stood among Kentucky tobacco and corn fields along the Ohio River. Its 325-MW unit went into operation in 1977, and a 525-MW unit was added in 1981. The plant staff were highly committed to keeping their plant running and their customers supplied with electricity. For more than two decades, the East Kentucky Power Cooperative’s (EKPC) Spurlock Station benefited from a maintenance-driven work culture staffed with experienced employees. Then change happened.

In the past 10 years, the plant’s rating, value, and complexity nearly doubled, and many other changes were introduced as a result of new equipment and technology, employee retirements, and new staffing. For example, in April 2005 Spurlock (Figure 1) dedicated a new 268-MW unit that uses a circulating fluidized bed process—a first for EKPC. That unit, known both as Unit 3 and the Gilbert Unit, ranks as one of the cleanest coal-powered units in the nation, but its operations and maintenance (O&M) challenges were quite different from those of the conventional units. Then in April 2009, Unit 4, another 268-MW unit, began operation.

|

| 1. Physical change spurred operational change at Spurlock. Through its work process optimization program, the Spurlock Station is embracing the challenge of change. Source: East Kentucky Power Cooperative |

As a result, the facility’s staff had to adjust to changing work procedures and culture. At the same time, the competitive imperative to generate power more efficiently required training and the standardization of work processes. All employees were called upon to meet and work through the challenge of change together.

Developing a WPO Culture

As part of the change in operations, Spurlock’s management collaborated with salaried and hourly personnel to design and implement work process optimization (WPO). Now, two years after that process began, their proactive, operations-driven culture is promoting continuous improvement at the facility. A revamped operator training program, the addition of six planners and four engineers, the integration of production teams, and a new computerized maintenance management system (CMMS) that is in development keep all employees aware that they can never go back to the old ways of doing their work.

As Spurlock staff have learned, time commitments and strong personal efforts from everyone are necessary in order for real change to be implemented. The station manager often shares his vision of “the desired future state” with station employees. That vision includes:

- Engineered solutions to problems and improvement opportunities—“continuous improvement.”

- Daily and weekly maintenance schedules.

- Dedicated planned outage resources.

- Responsibility-centered performance management.

- Employee development and succession plans.

- Close relationships among supply chain, warehouse, safety, fuels, and environmental teams.

- Multi-skilled production teams.

- Stronger technical and risk management evaluations.

- Enhanced financial tracking.

- Optimized staffing levels/contract resources.

Business drivers that are part of the desired future state vision include ensuring employee and plant safety; being environmentally compliant; reducing production costs through improved asset reliability and availability; and effectively managing labor, inventory, contractors, and fuel costs.

Building a Foundation for Change

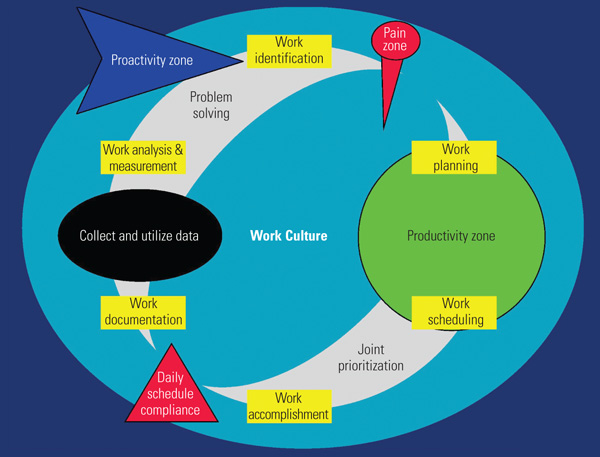

Following a work practices assessment, Spurlock Station formulated its new structured work process. Reliability Management Group (RMG), a work process consultant firm, assisted the station with WPO design, implementation, and field coaching. Spurlock Station management began their WPO efforts by developing management expectations for work process elements of the model shown in Figure 2.

|

| 2. How work process optimization works. The yellow boxes identify basic work processes, and the “wheel” illustrates how their interrelationships support efficient work practices and continuous improvement efforts. Source: Reliability Management Group |

With WPO management expectations in hand, the deliberations and design team—a cross-functional group of hourly, salaried, supervisory, and management employees—built additional detail into their preferred work process. Guidelines for the six processes (the yellow boxes in Figure 2), workflow diagrams, and measures were developed by consensus, documented, and then affirmed by management. The station had its roadmap for the change journey.

Implementing WPO

With station management’s commitment and corporate backing, the WPO implementation began in January 2009. This major undertaking was daunting and involved considerable resources, time, money, and energy. Plant personnel were transitioning from construction to commissioning and commercializing new operations, plus operating three existing units and handling multiple fuel sources. Four scheduled outages were also tucked into the calendar year. Managers weren’t crazy, but some employees wondered what would motivate them to undertake WPO in light of all that was going on at the station.

Operators and craft teams were frustrated by lost time, wasted effort, and bruised egos when assignments didn’t turn out as expected. They were expected to accomplish work on short notice with limited communication and coordination. Employees knew improvements were needed but wondered how their work lives would be affected. The WPO process invited them to share ideas and feedback, make changes through consensus, and communicate WPO successes and challenges—all of which was a new way of doing business. Not everyone agreed on what should change, and how. What’s more, the WPO steering committee’s initial project time line needed to be adjusted due to unexpected events.

Understanding the delays and frustrations, the station manager was steadfast in his leadership and persevered. “I believe the WPO implementation speed is justifiably slower than my other experiences (with implementations like WPO). Regardless, we will achieve our WPO goal,” Station Manager David Elkins commented.

The remainder of this article explains how Spurlock personnel dealt with a number of challenges in implementing WPO at their facility.

Managing Time

There isn’t enough time to do everything. From the newest to the most experienced employee, all station employees at some time during WPO implementation have been overwhelmed, overworked, and pulled in several directions. WPO is not a magic bullet; it’s a tool. Work scheduling helps maximize getting the right work done at the right time, but true emergencies will never be eliminated, only minimized.

Work demands are still heavy, yet gradually Spurlock personnel are using WPO as a tool to manage first things first. Today Spurlock staff are managing risk and resources more proactively than they did two years ago. Patience, effort, and communication (in groups and one-to-one) are required. Safely accomplishing the most important work for the station is the top priority of the staff, and focusing on the big picture helps put time pressures and station life in perspective.

Daily and Weekly Scheduling Processes

The work scheduling group was the initial action team in the WPO process and a very visible change for the station. Standardized formal scheduling now exists for six craft groups and a contractor crew. Employees are gradually seeing that the process is designed for a purpose: doing the right work at the right time with the right resources. Nonetheless, there has been and continues to be frustration with the changes that formal scheduling brought. Standardized scheduling required eliminating some old habits and adding important new behaviors for both managers and supervisors, such as:

- Calculating labor availability

- Keeping backlogs accurate

- Creating schedules

- Prepping for and attending scheduling meetings

- Measuring schedule compliance

Supervisors and back-up supervisors received one-to-one field coaching on the scheduling process. Field time revealed that supervisors did not need 5+ hours a day to properly complete schedules—it just felt that way to them.

Based on supervisory input, schedule formats were modified and reviewed with all users. Although they are less intense now, scheduling obstacles still exist:

- Outage work and emergencies compete with non-outage work for time and resources.

- The staff’s knowledge of Maximo (asset life-cycle and maintenance management software) and Excel are improving through more frequent use.

- Supervisors are transitioning from focusing on job details to overall work and schedule execution.

- Back-up supervisors are learning and are involved in the process, but this reduces their “wrench time.”

Agenda-driven weekly and daily scheduling meetings—the formal settings for work communication and coordination—are now more accepted and done more easily, but initially it was a struggle for both O&M supervisors. Under the current system, the schedules are posted electronically; supervisors are expected to post hard copy schedules in their respective work areas for crews to see. At day’s end, maintenance supervisors document actual hours of scheduled work done, whether or not the assignment was completed, and, if not, the hours remaining for completion.

Field coaching continues on proper, consistent use of the daily and weekly scheduling process. One supervisory challenge, which is allowed under the new system, is to say “no” to lower-priority, unscheduled work. Protecting the schedule allows the staff to complete scheduled work and appropriately respond to true emergencies. Basic work process tools and disciplines are the little things that must be ingrained so that the big things—safety, regulatory compliance, productivity, and reliability—continuously improve.

Proper Planning Introduced

Planning and scheduling processes are the main centerpieces of WPO efficiency. Maintenance job planning had been informal before WPO; supervisors, crafts crews, and technicians did their own type of planning before starting a job. “Planning” was simply getting the right materials from the stores, the right tools from the tool room, and the right employees with experience for the job. Furthermore, all this was typically done just as work was assigned. Spurlock’s management knew formal job planning by dedicated planning resources would increase maintenance productivity and reduce lost time frustrations and costs.

Planner candidates were identified from the maintenance department. Then RMG, the work process consultant that the EKPC staff partnered with, conducted a one-week training event on planning with participants from two EKPC sites. The training focused on using proven planning principles—such as scoping, estimating, engineering, collaborating, organizing logistics, and establishing timelines—to plan for scheduled outages in advance. Later, an outside technical resource helped planners with ideas related to equipment outage planning, and two planners attended a week of Fossil O&M Information Service training.

Currently, Spurlock Station has a planner in the materials handling department and five planners in the main plant. Plant assignments consist of one long-term planner and one short-term planner for Units 1 and 2, one long- term planner and one short-term planner for Units 3 and 4, and one planner for the electricians and the instrumentation and control team.

Planners became the planning action team and went right to work. They created planning tools; developed a project management review process; constructed a forced/reserve outage list for each unit so the highest priority work is ready to be worked on in the event of an unexpected outage; initiated a parts kitting and staging process with stores; and began having weekly planners’ meetings on Fridays.

Training for All Staff

Training is a significant factor in meeting the challenge of change. At Spurlock, new equipment, new processes, new employees, and new policies required everyone to participate in training.

An experienced operator reflected, “New scrubbers and two new units in the last five years meant operators were taking the controls of new assets that even the experienced operators hadn’t touched.” A manager asked himself, as a test, “If I was the only one here and something went wrong, would I know what to do?” During times of significant change, even experienced personnel occasionally work outside their comfort zones.

Currently, the training department’s focus is on operations. With the assistance of a training consultant, two training coordinators are developing simulator training materials, formalizing operator checklists, administering testing programs, maintaining operator progression charts, updating standard operating procedures, and training and auditing the new energy control program.

Computerized Maintenance Management System

An effectively used CMMS is a key tool for implementing and sustaining WPO efforts. Valid, timely data are needed for feedback on the process and for problem solving. EKPC corporate management is standardizing business software across all EKPC business units. The new system’s rollouts are scheduled to take place during the summer of 2010 at six locations. The supported functions included planning, supply chain, scheduling, and measurement.

Measure and Modify

Managers want to know how the WPO is working and what they can do to remove obstacles to improvement. For years, supervisors cited work interruptions, manpower shortages, and coordination missteps as being the problems that prevented work from getting done as quickly or as well as they hoped. Those obstacles remain, but the behavior modification is that now supervisors are supposed to document them, not just talk about them. This is a huge change that causes concern among supervisors, who wonder, “Will we be held responsible for events out of our control? What happens to me if I’m at fault?”

Measurement usually prompts such worries. To counter that concern, work process measures were introduced to managers and supervisors as tools to gauge WPO health, identify issues, and recognize progress. To reinforce measures as tools for continuous improvement, EKPC’s Senior Vice President of Power Production Craig Johnson said, “Having WPO means the finger of blame is not pointed at people, but at processes.” He wants EKPC sites to focus on refining and honing the right side (the efficiency) elements of the work process management model (Figure 2) in 2010 and focus on refining the left side (the effectiveness) elements in 2011.

Supervisors are positioned to be problem solvers if they use schedules effectively to answer questions like, “How well can I predict tomorrow’s work and next week’s work? What events impact this schedule’s results?” Formal scheduling provides methods to quantify schedule impacts by type, frequency, and hours. This information, in turn, becomes the business case for making changes and resolving issues. The process of schedule compliance compares hours and assignments scheduled versus what is actually accomplished; impacts are identified by variance codes. Schedule compliance measures are derived from the schedules supervisors complete throughout the week.

A variety of work process measures (leading indicators) and key performance indicators (lagging indicators) are reported. Collecting and reporting accurate, complete measurement data is a trial-and-error process as planners and supervisors improve the timeliness and accuracy of CMMS inputs and as new processes not yet measured are implemented.

The WPO steering committee’s future plans include physical measurement boards in work areas and meeting with employees for measurement question and answer sessions.

Organizational Participation

Corporate-initiated business processes, revised company policies, and station-initiated efforts contribute to WPO’s challenge of change. Implementing the following ongoing initiatives involves the participation of several employees:

- Revisions to the budgeting process, performance review process, and compensation policies.

- Selection of new business management software to replace the existing Maximo system.

- A new energy control program (the updated hold card procedure or lockout/tagout process).

- WPO joint steering committee composed of four EKPC sites to promote communication and standardization of WPO processes, measurements, and CMMS use across the generation teams (see sidebar).

- Supply chain interface to build station and supply chain relationships, lower EKPC costs, and increase reliability.

- Employee visits to Temple-Inland (a steam customer) and EKPC Dispatch, which handles supplying electricity to the grid.

Work Culture Change

Most employees understand the need for change. New construction has increased station capacity and, in turn, requires increased work process discipline for Spurlock to continue to be a safe, low-cost, reliable producer of electric power. Today’s experienced, long-term employees and new employees (both wage and salaried) need to work differently in some aspects of their jobs than they did in the past.

Employees who participated in deliberations and design sessions, have been involved with action teams, or attended scheduling meetings now are aware of WPO and probably have a greater sense of process ownership than those who haven’t had similar experiences. Although some employees may never totally buy into WPO, even those employees can probably appreciate the overall improvements resulting from certain new behaviors, such as:

- Writing a work order before the work is started instead of making a call or grabbing a technician.

- Knowing the hours of maintenance backlog instead of knowing only the number of work orders.

- Planners planning and supervisors supervising instead of anyone planning jobs when they have time.

- Planning jobs before they are scheduled instead of mechanics going to a job to see what they need.

- Using an updated forced/reserve outage list for each unit instead of remembering downtime jobs.

- Formal daily and weekly scheduling meetings instead of contacting people when and if the employee remembers.

- Maintenance personnel integrated with operations on rotating shifts instead of day-only maintenance.

- Documenting schedule compliance and variance codes instead of having a gut feel for schedule misses.

- Having formal work processes to follow instead of assuming who is supposed to do what next.

Continuing the WPO Journey

Work process optimization’s overall objective is to achieve the lowest cost maintenance through optimized work processes. The initial goals of WPO were to:

- Create a standardized, consistently executed work process.

- Improve communication and coordination between stakeholders.

- Increase the safety, efficiency, and effectiveness of the work being performed.

A year and a half into the significant effort to implement WPO, these goals are being realized at Spurlock. The desired future state is becoming a reality. A changeover to an operations-driven culture is taking shape. Employees now have greater opportunities to become involved and contribute to continuous improvement. Corporate and station management are committed to leading and sustaining the WPO initiative to achieve successful outcomes related to the bottom line and the work culture.

Considerable work still needs to be done. Nothing ever seems settled in an environment of continuous improvement and continuous change. Not all the questions have answers yet, and frustrations are partnered with successes. Some work processes are partially implemented, all processes need reinforcement, some employees need coaching, and a few action teams are still needed to complete the first pass through the work management process model shown in Figure 2. The WPO journey and the challenge of change continue.

—Joe VonDerHaar ([email protected]) is maintenance manager, Daryl Ashcraft([email protected]) is production team coordinator, and David Elkins ([email protected]) is station manager at EKPC’s Spurlock Station. Tyler Gehrmann and Arne Skaalure, Reliability Management Group consultants, contributed to this article.