Why Coal Plants Retire: Power Market Fundamentals as of 2012

Power companies in the U.S. have announced a growing number of retirements of coal-fired power plants over the past 12 to 14 months. While not unexpected, recent announcements have sparked debate over the causes of these business decisions, with some pointing to regulations issued by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) as the primary reason.

Putting aside the political context of the current debate, a closer examination of the facts reveals that the recent retirement announcements are part of a longer-term trend that has been affecting both existing coal plants and many proposals to build new ones. The sharp decline in natural gas prices, the rising cost of coal, and reduced demand for electricity are all contributing factors in the decisions to retire some of the country’s oldest coal-fired generating units. These trends started well before the EPA issued its new air pollution rules.

In general, the owner of a coal-fired power plant (or of any generating facility, for that matter) may decide to retire the plant when the revenues produced by selling power and capacity are no longer covering the cost of its operations. Though sometimes these decisions are complex, they essentially can resemble the basic choices that households face, for example, when they have to decide whether making one more repair on an old car is worth it; often, making the repair is more expensive and risky than the decision to trade in that car and buy a new one with better mileage and other features that the old car lacks.

These plant-retirement decisions thus turn on these economic fundamentals: Can the plant produce power at electricity prices that allow the owner to cover its operating and investment costs, including the ability to earn a reasonable return from the production and sale of electricity? It is these other considerations, beyond the EPA’s clean air rules, that have been influencing recent coal plant retirement decisions.

Electricity Market Dynamics

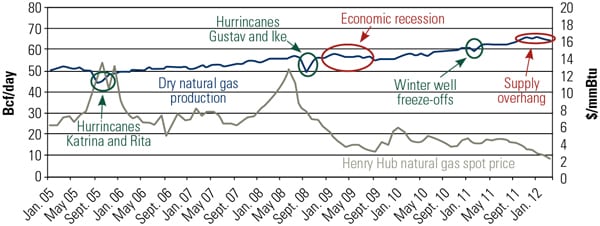

In today’s power industry, the profitability of many coal plants depends substantially on the difference in price between coal and natural gas. In competitive power markets like those in the Midwest, Mid-Atlantic, and Northeast, and even in more traditional power regions such as the Southeast, falling natural gas prices lead to lower revenues for coal plants by causing wholesale electricity prices to decline. Rising coal prices can further narrow the margins of coal plant operators. In the past year, coal plants have been facing a perfect storm of falling natural gas prices, a continued trend of high coal prices, and weak demand for electricity (Figure 1).

1. The fuels used to produce electricity are responding to market conditions—rising coal prices and dropping natural gas prices. Source: EIA

Natural gas prices have fallen to record lows, reducing the wholesale price of electricity in most of the country’s power markets. Natural gas prices fell from $4.37/MMBtu in 2010 to $3.98/MMBtu in 2011, to under $2.00 in May 2012. The average NYMEX spot price was $2.87 in mid-July. The result has been a significant drop in wholesale power prices. Wholesale electricity prices have dropped more than 50% on average since 2008, and about 10% during the fourth quarter of 2011. The record low natural gas prices are attributed to strong domestic production, robust storage levels, and new pipeline projects that have allowed additional supplies to get natural gas to markets (Figure 2).

2. U.S. production of natural gas has been steadily increasing since late 2005 but has lately leveled off. The red ovals on the chart illustrate periods when natural gas production leveled off during a period of falling natural gas spot market prices. The first was during the economic recession. The latest began in the fourth quarter 2011 and continued through the first quarter of 2012. Natural gas prices continued to fall through the first half of 2012. Source: EIA

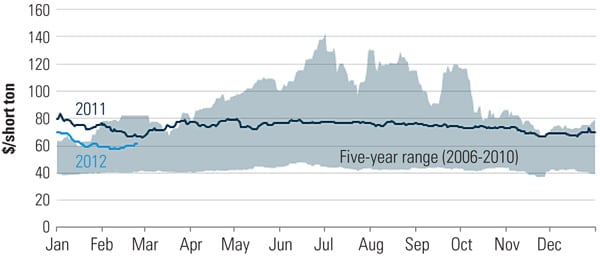

At the same time, coal prices have remained relatively high: According to the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA), "Delivered coal prices to the electric power sector have increased steadily over the last 10 years and this trend continued in 2011, with an average delivered coal price of $2.40 per MMBtu (5.8 percent increase from 2010)." The price of coal during early 2012 dropped sharply due to a warm winter and low natural gas prices (Figure 3).

3. Central Appalachian NYMEX coal futures prices, $/short ton. Source: EIA

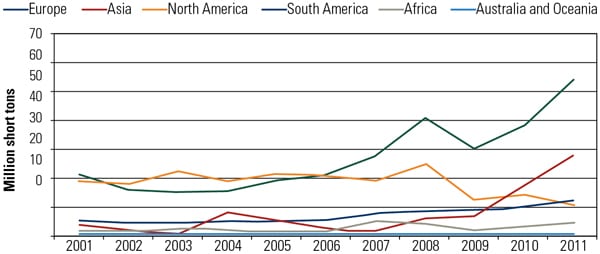

Coal prices have pushed upward in part because exports have offset a drop in domestic coal consumption. The Appalachian region, in particular, saw a large increase in exports last year, driven by demand for metallurgical coal used in steelmaking. U.S coal exports increased 31% in 2011, the highest level since 1991 (Figure 4).

4. Coal exports to European and Asian markets represented 76% of total U.S. coal exports in 2011. In 2011, coal exports were up 31%, largely to rising exports to Europe and Asia. Source: EIA

The surge in exports was driven in part by reduced production in other parts of the world. Flooding last year disrupted coal mining in Australia, the world’s largest coal exporter, contributing to increased U.S. coal trade with India, Japan, and South Korea. Coal exports are expected to remain strong in response to global energy demand. Arch Coal, for example, announced in a news release of February 10, 2012 that it had made several investments in 2011 to bolster its U.S. export capabilities.

The tighter price differentials between natural gas and coal in recent years have squeezed the financial performance of many coal plants, especially the older and less efficient ones. To illustrate, the power supply curve in the figure below indicates that in the PJM region (shown here as the RFC (ReliabilityFirst) region), coal-fired power plants dispatched at higher prices in 2010 compared to 2007, with the reverse true for natural gas-fired power plants.

In this regional power market, the revenues for plants reflect the selling price of the last plant dispatched to meet loads. So, for example, a coal plant dispatched at a 125,000-MW level of demand sold power at $24/MWh in 2007. At a higher demand level (say, 150,000 MW) that same year, the clearing price would be $56/MWh, set by the dispatch of a natural gas plant. In that high-demand hour, the referenced coal plant would receive revenues of $32/MWh (reflecting the $56/MWh clearing price, less the coal plant’s own production cost, including fuel, of $24/MWh). By contrast, in 2010, the coal plant dispatching at a 125,000-MW demand level sold power for $32/MWh, while the gas plant dispatched at a 150,000-MW load level was selling at $40/MWh. In 2010, therefore, the referenced coal plant would receive net revenues of $8/MWh in that high-demand hour (Figure 5).

5. Dispatching is largely determined by the plant owner’s fuel cost. Source: Data from SNL Financial for 2007 and 2010 for the Reliability First Corporation region

[END ART]

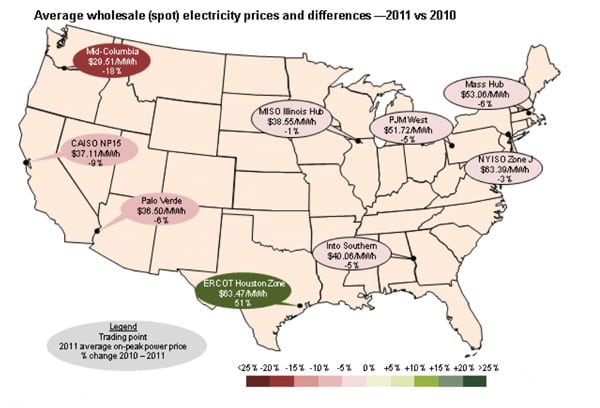

Across the course of a year (as in 2010 and 2011), these much tighter gas-coal price differentials put significant price pressure on the least efficient coal plants. Net revenues were down in the hours they operated. And in many cases, system operators were dispatching more gas-fired power plants ahead of these less-efficient coal plants. The map in Figure 6 shows that with the exception of the ERCOT Texas market, average wholesale electricity prices were lower in 2011 than 2010.

6. Wholesale electricity prices dropped in 2011 across much of the U.S. due to lower natural gas prices. Source: EIA

Several companies that have traditionally relied on coal for a substantial portion of their generation are using more natural gas. In its Q1 2012 earnings call (Apr. 20, 2012), AEP’s executives reported that the company’s natural gas consumption had increased 62% year over year, and that with the exception of one plant, its gas-fired combined cycles in the eastern part of its system were operating at an 85% capacity factor. In an interview in National Review ("War Over Natural Gas About to Escalate," May 3, 2012), AEP’s CEO said that the company increased its overall "natural-gas capacity by 24 percent last year, and it expects to increase that by another 14 percent this year. . . . At the peak of 2007 and 2008, we were taking [and burning] about 80 million tons of coal a year. . . . Today, that’s probably down to the order of 55 million tons of coal a year."

Similarly, Southern Co. executives recently reported on their Q1 2012 earnings call (Apr. 25, 2012) that in 2007, the company’s electricity production was 16% natural gas and 70% coal. They now expect that the mix for 2012 will be 47% natural gas and only 35% coal. Its natural gas combined cycle plants have been operating at a 70% capacity factor, and the company estimates that its purchases of natural gas made up 2% of total gas consumption in the U.S.

These changing natural gas and coal prices have contributed to coal-fired electricity generation dropping by 13% from 2007 through 2011, while gas-fired power production increased by 13% in the same period, according to the EIA’s Short-Term Energy Outlook, released February 2012 (Table 25).

Lower Demand for Electricity

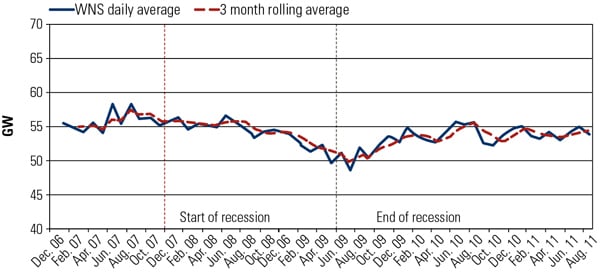

On top of the economic pressures brought by lower natural gas prices, electricity demand has been muted due to the sluggish economy, increased competition from demand-side resources, and the mild winter weather. For operators of the least-efficient coal plants, in particular, these factors are further aggravating their financial situation (Figure 7).

7. This graph of weather non-sensitive load (the estimated peak load after removing the weather effects from actual peak load) in the Midwest (MISO) region indicates the underlying trends in demand from economic and demographic factors. Source: Midwest ISO, "MISO 2011 Summer Assessment Report: Information Delivery and Market Analysis," Oct. 19, 2011

Low demand for electricity moderates electricity prices by reducing the amount of time a relatively inefficient coal plant might otherwise be called upon to operate. In 2009, electricity consumption by industrial customers was at its lowest point in 10 years, according to FERC’s "Winter 2011-12 Energy Market Assessment," released Oct. 20, 2011.

Although consumption has increased since then, it still remains below the levels prior to the economic collapse in 2008. As shown in Figure 7, excerpted from an assessment prepared by the Midwest ISO (MISO), electric loads (demand) in the heavily industrial Midwest power region declined in 2008 to mid-2009, followed by a gradual recovery since then.

Reduced demand for electricity has led companies to cancel some new power projects and idle existing plants. In an extreme case, Great River Energy mothballed a recently constructed coal-fired power plant in North Dakota. The plant was fully equipped with modern pollution control systems, but the owner has opted not to run the facility because of low demand for electricity and low power prices.

Energy efficiency and other demand-side resources have also played a role in moderating electricity prices. In PJM, the nation’s largest energy market, demand response and energy efficiency contribute a growing share of new capacity in the market’s forward capacity auction. Demand response, energy efficiency, and renewable resources made up about 10% of the resources clearing PJM’s 2014–2015 capacity auction, according to a May 13, 2011, news release ("PJM Demand Resources and Energy Efficiency Continue to Grow in PJM’s RPM Auction"). These resources were offered into—and accepted by—the market at prices lower than other competing generating resources that did not clear in the auction. Such resources contribute to the economic pressure on existing generating resources.

Although recent summer periods have been hotter than usual (notably in Texas), based on Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) data for cooling degree and heating degree days, the U.S. and Canada experienced one of the warmest winters on record, reducing energy demand and exacerbating the financial conditions of many generators. The two-month period from December to January was the fourth-warmest on record, according to a National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Feb. 7, 2012, press release ("January 2012 the fourth warmest for the contiguous United States").

Minnesota experienced record warm temperatures for the winter period, with an average temperature 10.1 degrees F above average, according to FERC data. A total of 22 states from Montana to Maine had December to January temperatures ranking among their 10 warmest. Lower temperatures have contributed to lower natural gas demand, further dampening natural gas prices. Lower temperatures have also reduced the demand for electricity. The charts in Figure 8, published by the EIA on Feb. 15, 2012, illustrate the unusually low winter power prices experienced from November through the first week in February in the Northeast and Midwest, resulting from the warm weather.

8. Warm weather, low natural gas prices hold down winter power prices in the Northeast and Midwest. Source: EIA

Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA), the nation’s biggest government-owned utility, attributed a 14.8% reduction in residential electricity consumption to the mild winter, according to "Mild winter pushes Tennessee Valley Authority in the red," published by Chattanooga Times Free Press on Feb. 4, 2012. TVA power sales in the fourth quarter of 2011 were cut by $260 million compared with the same quarter a year earlier. Electric demand in the residential sector is more sensitive to weather than in the industrial sector.

Recent Corporate Announcements

On Jan. 26, 2012, FirstEnergy Corp. announced plans to retire six older coal-fired power plants in Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Maryland, citing the EPA’s mercury and air toxics standards as the cause. Other facts suggest that market conditions, combined with the remaining useful life of the plants, played a significant role in the company’s decision. Most of the retiring units are between 50 and 60 years old. They are all "merchant" power plants, whose financial performance is shaped by competitive power markets. FirstEnergy had already idled most of these units beginning in 2010 because of reduced demand for electricity and the need to reduce operating costs.

FirstEnergy’s prior decision to retire the units by Sept. 1, 2012, suggests that market fundamentals led the company to reach the conclusion now, rather than closer to the date on which the company would need to comply with the EPA’s mercury and air toxics rule (which is March 2015, at the earliest).

FirstEnergy has made similar decisions to retire older units in the past:

- Rockaway (Ohio): demolished in 2008

- Mad River Plant (Ohio): closed in 1981

- Gorge Plant (Ohio): mothballed in 1991

- Toronto Plant (Ohio): closed in 1993

- Edgewater (Ohio): closed in 2002

A second example is American Electric Power’s June 2011 announcements of coal plant retirements. Although the EPA regulations were cited in the press release announcing the retirement of nearly 6,000 MW of coal plants, market dynamics and practical business decisions played an important role. AEP’s CEO had told financial analysts at an investor conference the prior week that those coal plants were "high cost plants" and "in fact, throughout I think almost all of 2009 those plants probably didn’t run 5% of the time because natural gas prices were such that they simply weren’t dispatching. When we shut those down there will be some cost savings as well." In 2007, AEP had signed a consent decree covering many power plants, including all but one of the units in the 2011 retirement announcement; in that consent decree, relating to prior environmental litigation surrounding the plants, the company had already agreed to retire, retrofit, or repower 4,500 MW of these plants.

Since the EPA issued the final Mercury and Air Toxics Standards (MATS) rule, AEP has reported to investors that it has reduced its projected environmental compliance costs because of flexibility that the EPA has provided in terms of the particulate matter standards. AEP has also reduced its planned coal unit retirements. According to AEP CEO Nicholas K. Akins:

[A]s we go through this process, we originally looked at 6,000 megawatts being retired. I think now it’s 5,200, since Big Sandy will stay online. But we also projected that we would replace that with about 1,500 to 1,800 megawatts of natural gas-fired capacity, so if this fuel switching is going to continue to occur, we’re going to retire units that are out of the market as quickly as we can. And then as far as replacement with natural gas facilities, that’ll be primarily the fuel of choice for us, because in our eastern footprint, we never had that really before, but now we have substantial pipeline capability and the advent of the Utica and Marcellus shale has just dramatically changed the way we look at natural gas in the future.

AEP management also told investors that the economic outlook in the 11 states where the company operates remains modest, with slight growth year-over-year expected in industrial and commercial sectors and flat residential load.

Other Factors Affecting Coal Plant Economics

New environmental requirements can put financial pressures on coal plant operators, but power market fundamentals, and especially tightened gas-to-coal price differentials and lower electricity demand, have contributed significantly to the recent business decisions of some coal plant owners to retire some of their marginal plants. Many market observers report continued pressure on the coal fleet in the near term, at a minimum, due to these economic drivers.

The timing of particular power plant retirement decisions may be triggered by other factors that affect the circumstances of a particular plant or a particular company. For example, a plant with marginal economics due to fuel market pressures might be tipped into retirement at the point when the company faces a maintenance-cycle milestone that would require a large investment just to keep the plant open for business. Similarly, a company might be facing more generalized workforce consolidation or labor agreement issues that contribute to the timing of closures of marginal plants. Companies sometimes time the announcements of closures to take advantage of tax opportunities or other matters affecting earnings in a particular financial reporting period. These triggers may not be as transparent as more obvious factors such as lower output levels and lower revenues received by certain plants, but they may affect the timing of some plant retirement events or announcements.

—Susan F. Tierney, PhD is managing principal for the Analysis Group Inc. Dr. Tierney is an expert on energy policy and economics, specializing in the electric and gas industries. She is also a former assistant secretary for policy at the U.S. Department of Energy and state public utility commissioner.