The Value of a Knowledge-Based Culture Grows in Lean Times

Given delays and cancellations of new generating capacity, pushing the existing power generation fleet is more important than ever. At ELECTRIC POWER 2009, multiple presentations explored the premise that an active knowledge management strategy — requiring a blend of digital and human elements unique to each power plant — will help you extract the most productivity from your assets.

As knowledge management (KM) becomes a discipline all its own, as did "total quality" in earlier decades, it’s easy to dismiss it as the latest management fad. At the same time, so many of the issues power plants face can be confronted with a sound KM strategy.

Managing a thinly staffed facility, retaining knowledge in the face of a more mobile workforce, integrating the myriad software and monitoring and diagnostic (M&D) and performance measurement tools into a coherent whole, and creating a healthy relationship between the plant and corporate work environments are all assisted through KM. At ELECTRIC POWER 2009, one session, and a presentation from a second session, agreed on the premise that KM offers cost-effective solutions for extracting more productivity from plants in lean times.

Digital Asset Intelligence

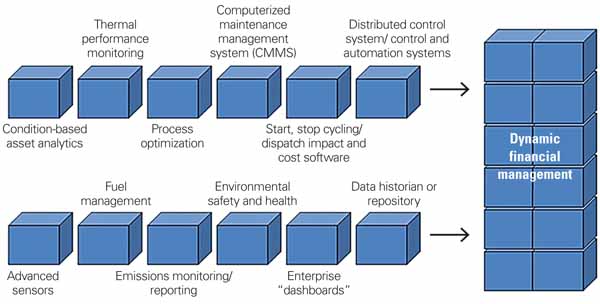

The first presentation, by Jason Makansi, Pearl Street Inc., and Paul Kurchina, KurMeta Inc., set the stage. Over the past few years, Pearl Street Inc. has visited several power stations, conducted surveys of plant managers, facilitated the ELECTRIC POWER Conference Plant Managers’ Forum, participated in software user forums, and interacted with plant managers at the HRSG Users’ Conference. The objective has been to progressively learn, and respond to, what plants like and don’t like about their control and automation systems, M&D software packages, and work and task management software — and to learn how they are being used, or not used. One overwhelming conclusion is that the various digital applications are still mostly "islands of automation" that are not integrated into a digital asset intelligence system or strategy (Figure 1).

1. Knowledge management building blocks. Islands of automation and analysis at the plant need to be integrated into a seamless whole. Source: Pearl Street Inc.

At the same time, there is a relentless drive from corporate headquarters toward fleetwide monitoring and enterprise resource management of plant information, and for good reasons. Cost pressures are relentless, new capacity is increasingly being put on hold, carbon is being monetized through taxes or cap-and-trade legislation, cyber-security looms as a new regulatory requirement, and staff realignments continue unabated as the pool of specialized, experienced talent continues to shrink.

To manage the digital side of the house, Kurchina and I presented highlights of the strategy contained in our 2008 executive white paper, "Brains and Brawn: Integrating Digital and Human Asset Intelligence into Comprehensive Power Plant Knowledge Management." It starts with this central idea: Digital asset intelligence (DAI) should be thought of as distinct from the physical assets. Just as the industry thinks in terms of a "boiler island" and a "turbine island," getting the most from digital technology means conceiving of a comprehensive digital asset intelligence "system." Those trained in mechanical, electrical, and chemical engineering disciplines also need to be educated and trained in the corresponding digital systems that will serve the physical plant. The reverse is true as well.

We went further and suggested that the organizational chart be reconfigured for DAI, including a chief asset intelligence officer at the executive level, asset intelligence architects at the design and engineering level, and asset intelligence specialists at the plant level (Figure 2). The DAI system that will serve a plant throughout its life needs to be designed in the aggregate as the plant is being designed. Like the physical assets, it will require maintenance, upgrade, replacement, and enhancement as the plant ages and technology changes. We believe this is the most efficient overall strategy for blending digital and human elements of knowledge management in a way that satisfies corporate objectives and resources typically available to plant staff.

2. Digital assets needing human management. Digital asset intelligence executives, managers, and specialists need to be built into the organizational structure of a generating company. Source: Pearl Street Inc.

Tie-in from POWID Nuclear Sessions

Coincidentally, a presentation from the colocated ISA Power Industry Symposium (POWID), echoed several of our points. James H. Flowers of Southern Nuclear Operating Co., Birmingham, Ala., in his paper and presentation, "Non-Technical Issues Impacting Digital Upgrades," referred to the "development of a hybrid digital expert who is trained in software and communications as well as mechanical and electrical theory." Referring to nuclear plants, Flowers noted that few managers have a strong background in instrumentation and controls (I&C), much less digital controls. This makes it difficult for them to make funding decisions related to digital technology.

But the issue is acute at the engineering level, too. Flowers cited the following example: A plant installs a new transmitter. An I&C designer, with independent verification, develops the design and orders material. Maintenance sets up a test plan and sets up the instrument. This is all rather mundane. Now take the transmitter and send its output to a digital control system. This complicates things. People familiar with traditional I&C design, installation, and maintenance are unfamiliar with writing software, testing it, and establishing communications between the transmitter and processor. Those with the software and network skills are usually located in the IT or computing department.

Specialized training is required to cultivate hybrid digital experts, and that training must cover the different phases of the equipment or system life cycle — design, testing, implementation, and maintenance. Unfortunately, there are few, if any, education or training programs that integrate all of these skills. Therefore, organizations have to develop digital hybrid experts internally through creative means. Some ideas are:

-

Create digital groups and work practice areas, not just for software portions of projects but for maintenance, design, and operations as well.

-

Apply ISA, Electric Power Research Institute (EPRI), and company or internally developed training classes.

-

Read and understand regulatory guides and licensing requirements from IEEE, the Nuclear Energy Institute, EPRI, the Institute of Nuclear Power Operations, and the Nuclear Regulatory Commission.

-

Develop industry-wide programs to support digital applications, especially in software development, software testing, software quality assurance, configuration management, cyber-security, and electromagnetic interference and radio frequency interference.

Although nuclear plants lag behind fossil and other plants in digital applications, many of Flowers’ ideas are just as relevant to other plants (see p. 29 for more details). In fact, many software companies supplying to the fossil power industry are inhibited by the lack of domain experts on their staffs and the lack of digital experts on the plant owner/operator staff. This is an inter-organizational gap on the fossil side rather than the intra-organizational gap to which Flowers referred. And no one needs to explain to power plant staff the organizational and cultural gaps between operations and maintenance and the corporate IT departments.

Software Integration

Phil Flesch, manager, power team at SmartSignal Corp., also addressed the asset intelligence "islands" theme based on SmartSignal’s experience. SmartSignal provides the predictive analytics that power the 24/7 monitoring of over 18 GW of generation, and those systems have been implemented over the past six years. Flesch discussed how, together with partners OSIsoft and General Physics Corp., his firm is working to routinely integrate three of the asset intelligence islands: predictive analytics, thermal performance monitoring, and data infrastructure.

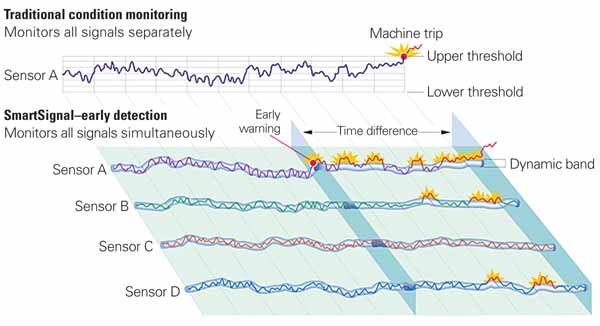

That integration is needed has been confirmed by data distilled from the Pearl Street surveys and interviews. Plant personnel are overwhelmed by data and alarms (see story p. 38). SmartSignal’s solution seeks to cut through the "data fog" to provide early detection of machine problems. In traditional condition-monitoring techniques, signals are monitored separately. SmartSignal’s software, in contrast, monitors all the signals simultaneously, correlates the data in real time, and provides alerts and warnings (Figure 3).

3. Early-warning system. Predictive analytics software monitors multiple signals and correlates them to provide early warning of problems and failures. Source: SmartSignal

An interesting point about digital intelligence developed through predictive analytics and confirmed by the many monitoring centers that employ SmartSignal is that early warning identifies machine-caused as well as human-caused problems. The agreed-upon ratio, from monitoring center managers, is that problems at a plant typically are equally distributed between human-caused and machinery-failure problems, which suggests an additional, interesting dimension to asset intelligence.

A new SmartSignal product, CycleWatch, will extend the company’s monitoring solution from "steady state" conditions to the dynamic start-up cycles for gas turbines (GT) and combined cycles. The rapidly changing conditions of GT-based plant start-up provide the earliest indications of failures, such as with sensors, combustors, nozzles, and valves. SmartSignal’s advanced (and patented) variable state similarity based modeling (VBM) technology is able to account for the chaos of start-up and point out just what is starting to deviate from expected behavior.

In addition, SmartSignal is working to close the gap among the different islands of analysis. Its software represents the front end of problem detection. Its customers also rely heavily on OSIsoft’s visualization tools, such as PI ProcessBook. Another new product, which was launched in 2009, SmartSignal xConnector, will replicate SmartSignal’s modeling information and incidents back into the PI environment from which the original data are read. This will allow customers to see the information within the graphical PI screens they prefer. Addressing the issue of intelligence islands eases pressures on power plant staff.

Functional Integration

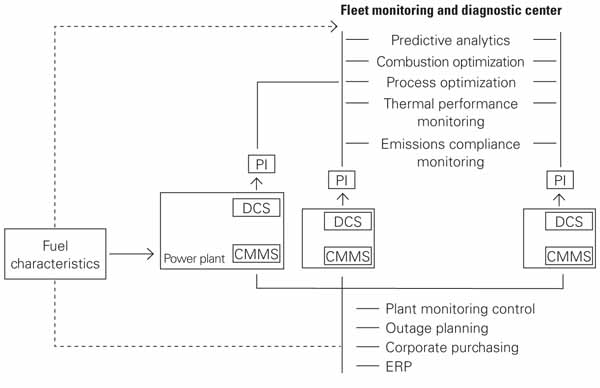

Ross Convey, OSIsoft, showed how the application of his company’s plant-level data infrastructure software — so prevalent in power stations that it almost can be considered a de facto standard — is being expanded to an enterprise architecture platform "from fuel to meter." OSIsoft seeks to evolve into the common data infrastructure for generation, transmission, and distribution, and more recently, even advanced metering infrastructure. In recent years, OSIsoft has been supplying its solution suite to independent system operators around the U.S. and is demonstrating its software as a key smart grid component.

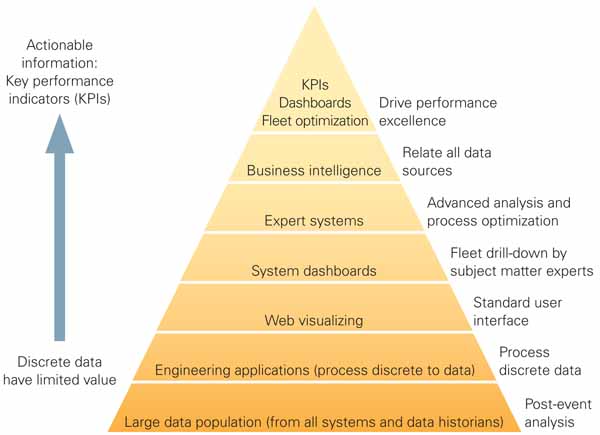

Many important power station applications from other software vendors, SmartSignal included, draw data continuously from OSIsoft’s PI system for individual plants and entire fleets. Many utilities today have taken a fleet-centric approach to managing their assets, facilitated by digital asset intelligence. Convey discussed how one leading utility, DTE Energy, uses OSIsoft PI to collect data and distribute actionable information through OSIsoft’s Process Book displays and a variety of third-party applications (Figure 4).

4. From data to actionable information. Performance excellence is driven through the organization via a hierarchy of knowledge management databases, software, and applications. (Diagram was simplified from original presentation version for clarity and general application.) Source: DTE Energy

The Human Element

Dr. Robert Mayfield, plant manager of Tenaska Virginia Power station (a 2007 POWER Top Plant recognized for its training and management practices), recently completed his doctoral dissertation in power plant knowledge management. Mayfield, who focused his presentation on the human element, asked and answered these questions:

-

Are you determining what critical knowledge is needed at your plant?

-

What knowledge is available and what is missing?

-

Who needs this knowledge?

-

How will the plant or organization retain this knowledge?

-

How will this knowledge be applied?

Most of Mayfield’s presentation was directed at maintaining a knowledgeable and motivated workforce. He made the point that organizations that are superior at sharing knowledge are not necessarily those with the best technology infrastructure. One common malady is knowledge silos, or people or departments that hoard knowledge as a defensive strategy. Interestingly, knowledge silos are also built up around the "islands of automation" discussed above.

Mayfield advocated a formal knowledge management program to "promote an integrated approach to identifying, retrieving, evaluating, and sharing an enterprise’s tacit and explicit knowledge assets to meet strategic objectives." To distinguish between tacit and explicit knowledge, he used a baseball analogy. Explicit knowledge encompasses the hard rules of the game — there are three outs per team per inning, nine innings constitute a game (unless there is a tie), three strikes are an out. Tacit knowledge involves such things as how fast the pitches are coming to the batter and the amount of time a batter has to discern which pitch (curve, slider, fast ball) is being thrown. Tacit knowledge involves watching films of the opposing team and learning their practices and habits to gain insight that makes you more competitive against them.

Tacit knowledge at the plant level is "mainly in the heads of the experts or the experienced hands." Therefore, it has to be actively and continuously drawn out for the benefit of others in the organization. Some of Mayfield’s suggestions for doing that include: creating communities of practice, a concept that has been applied successfully across nuclear power stations; brainstorming sessions; video and audio conferences; and participation in industry user groups.

Although Mayfield distinguished the technology element from the human element, aspects of his knowledge management program have technological dimensions. One is centralized and remote monitoring and control. Mayfield called these "centralized smart stations." At these "stations," many people with functional responsibility for the assets can share in the data and the analysis that converts data into information. In addition, Mayfield advocated the use of hand-held digital devices to display photos and diagrams that help maintenance workers in the field. Finally, he suggested that plant organizations encourage fleetwide communities of practice that can share knowledge and expertise through an intranet.

—Jason Makansi (jmakansi@ pearlstreetinc.com) is president of Pearl Street Inc., a technology deployment services firm.