The Coal Patrol: Looking Back at 2006

To borrow shamelessly from Charles Dickens, one of my favorite authors, for coal in 2006, "It was the best of times, it was the worst of times."

No Escape

The year began in horror. On January 2, most likely a result of a severe lightning strike, methane gas in the International Coal Group’s Sago Mine in central West Virginia ignited. The resulting explosion killed 12 miners. The rescue crew found one miner trapped underground for more than 40 hours. Mercifully, he survived.

Mine safety was the agonizing downside of 2006 in coal (Figure 1). Just over two weeks after the Sago disaster, a fire in West Virginia’s Alma No. 1 mine, in Logan County, claimed two more miners’ lives.

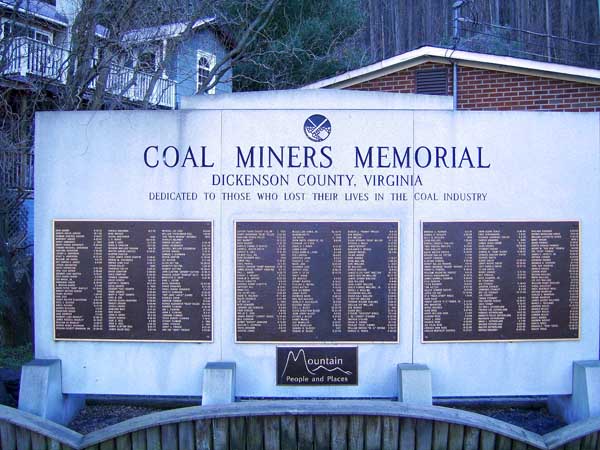

1. A memorial to all the coal miners who have died in Dickenson county, Va.–on the border with West Virginia–was recently dedicated in Clincho. The Sago mine is in Upshur County, W. Va., Courtesy: Dickenson County

January 2006 was the harbinger of a nasty year for coal mine safety. According to the U.S. Mine Safety and Health Administration (MSHA), 2006 saw 47 coal mine fatalities, the worst record in many years. According to MSHA records, in 2002 there were 27 coal mine fatalities.

The record number of deaths in U.S. coal mines last year — 37 in underground mines and 10 in surface mines — was the reversal of a trend that saw 15 underground fatalities in 2002, 15 in 2003, 14 in 2004, and 13 in 2005. That’s very troubling. The coal mine death toll was the highest since 1995. Coal mine fatalities and injuries had been on a steady decline since passage of the Coal Mine Health and Safety Act in 1969, in response to the horrific 1968 Farmington mine disaster in West Virginia, one of the worst in U.S. history.

Sago may have been an artifact of bad luck: 17 miners died in methane gas or coal dust explosions in 2006, versus three from 2002 to 2005, according to MSHA data. Gas explosions are rare, but usually major, events. Most coal mining fatalities come incrementally in small numbers from roof falls in underground mines and heavy equipment – related accidents above and below ground, according to the MSHA.

But the pitiful 2006 safety record could also be the result of lax enforcement, as coal labor and some outsiders plausibly argue. Enforcement has been trending downward, and the MSHA has largely been leaderless during the Bush administration, which has not made mine safety a priority.

Ironically, the MSHA’s miseries are at least partially caused by congressional Democrats, who refused to approve the Bush administration’s nominee to head the MSHA. Richard Stickler, a veteran mine regulator from Pennsylvania, was well-qualified to head the agency, but Congress (for political reasons related to grandstanding after Sago) stalled the nomination. Bush gave Stickler a recess appointment last October. That ended when the 110th Congress convened in January, so the MSHA is again without a permanent head.

It is also worth noting that, historically, coal mining, particularly underground mining, has become a much safer job. According to the National Mining Association (NMA), in the modern era — 1984 to today — the number of U.S. coal mines has fallen from 3,496 to 1,400, and the number of miners has dropped from 178,000 to 82,000. Yet production has risen from 896 million tons in 1984 to an estimated 1.2 billion tons in 2006, the highest in the coal mining industry’s history. And injuries and fatalities have fallen far faster than productivity has risen. Coal mining, according to the U.S. Department of Labor, is now less dangerous than construction work.

Improving Conditions

A major part of the story of coal mining is increased productivity. It has two main causes: a shift of production to surface mines in the Powder River Basin (PRB) and the increase of long-wall mining in eastern and midwestern underground mines. Other contributors have been improvements in equipment O&M, communications, and haulage. The productivity improvements have not come from cutting corners on safety.

Nonetheless, the fatality figures are unacceptable. It is clear that the Bush administration, distracted by war and other foreign adventures, had not — at least until the Sago catastrophe — taken mine safety seriously. It was not on their political radar screen.

Congress and the Bush administration responded to the early 2006 tragedies with the 2006 Mine Improvement and New Emergency Response (MINER) Act, passed in June. Many on the labor side of the issue said the measure was too lax, filled with empty rhetoric and little action.

From industry’s point of view, the MINER bill was overkill and overly expensive. Massey Energy CEO Don Blankenship, who spent millions of his own fortune trying, unsuccessfully, to elect Republicans to the West Virginia legislature, was a harsh critic of the new federal legislation. "A lot of politicians are simply trying to gain favor and a lot of the others involved simply don’t understand the issues," he told the Associated Press.

Blankenship represented the industry’s chafing that regulators were focusing on requiring mine operators to supply underground air rescue packs based on 20-year-old technology rather than on newer air-breathing technologies. His view is shared by Consol Energy and Peabody Energy as well as the United Mine Workers of America.

The industry and the union, in rare agreement, are lobbying for more federal funds for mine safety. Although Congress gave the industry $10 million for safety research in the 2006 fiscal year, neither the NMA (the coal industry’s lobby) nor the UMWA believe that is enough. Said the NMA’s long-time safety lobbyist, Bruce Watzman, "When you talk about covering breathing technology and refuge chambers and seals and tracking technology and communications, $10 million doesn’t go very far."

Best of Times

Though 2006 was a nasty year for coal mine fatalities, it was a stellar year for production, prices, and industry profitability. According to the NMA, 2006 coal production is likely to total 1.15 billion tons — just below the 1.3 billion ton record of 2005. U.S. coal production has been at the 1 billion ton/year mark since 1994, after first hitting it in 1990 and then falling back under it in 1994.

Coal’s economic fundamentals are strong. Demand for the dusty diamonds is growing as the U.S. appetite for electricity climbs steadily. Utilities are planning many new coal-fired plants to meet growing demand for electricity in the lowest-cost fashion.

Financially, the industry did very well in 2006. Coal prices held up well, making coal the clear choice over natural gas or nuclear for new power plants. Coal companies are producing solid profits and reinvesting heavily in new production and upgrades at existing mines. In 2006 a number of utilities made major bets that coal would be the future of baseload generation, including an exceptional wager by Texas-based TXU on 11 new coal-fired plants, totaling 9 GW of new capacity, in the years to come.

There’s no doubt that coal will capture the bulk of the market for new baseload generation in the years ahead. The DOE’s National Energy Technology Laboratory says U.S. generators plan to build 154 GW of new coal plants over the next 24 years, and 50 GW over the next five. During the past five years, 6 GW of new coal capacity came on-line. How much nuclear baseload capacity powered up over the same period? Zero megawatts.

Dealing with one of its known critical issues for the future, the coal supply industry is aggressively looking for new miners and mine engineers to support increased production and replace the baby boomers who are beginning to retire in substantial numbers. That’s a real challenge for the industry and the union, but it is one that they have faced before.

Another plus for 2006 was that, despite the safety problems, the industry saw labor peace. That’s also the forecast for the coming year. At the end of December, the UMWA ratified a new contract with the Bituminous Coal Operators Association by an 80% vote. Cecil Roberts, UMWA president, said the vote was historic. "Never before has a contract been ratified by such a wide margin," he said. Roberts added, "In an era when workers in other industries are being confronted with significant cuts in health care benefits and pension benefits — if they can hang onto those benefits at all — this agreement represents a significant departure from that trend." A healthy industry means a good life for miners.

Removing Bottlenecks

Another positive development for coal producers and their utility customers in 2006 was the apparent elimination of the bottleneck in moving coal by rail east from the southern Powder River Basin in Wyoming. A May 2005 derailment on the track jointly used by the Union Pacific (UP) and Burlington Northern Santa Fe (BNSF) Railroads (Figure 2) had seriously disrupted PRB coal shipments to eastern, midwestern, and southern utilities for more than a year.

2. A Burlington Northern Santa Fe coal unit train rolls out of the Powder River Basin. Courtesy: Association of American Railroads

The problem seems to be solved. The Association of American Railroads (AAR) reported in December that "the so-called crisis in coal supply is over. The nation’s freight railroads are more than meeting the burgeoning demand for coal by electric utilities."

Having removed the Powder River Basin from its reliability watch list, the North American Electric Reliability Council late last year reported that winter coal inventories at power plants are in good shape. Said AAR CEO Edward Hamberger, "Railroads are investing heavily in expansion projects, including out of the PRB, so that we can handle even larger volumes in the future."

Another indication that the transportation bottleneck has been solved was the mid-January 2007 report by Union Pacific that it moved 194 million tons from the Southern Powder River Basin during 2006. That’s a new record for the UP and an increase of 15 million tons over 2005. The number of trains carrying coal from the Southern PRB on the UP increased by 895. On average, each train carried just over 15,000 tons, an increase of 200 tons over last year’s average, said the UP.

Laying More Track

More good news for coal consumers may have come from the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 8th Circuit in Minneapolis at the end of the year. The court denied a challenge by the city of Rochester, Minn., to a $6 billion expansion by the privately held Dakota, Minnesota, and Eastern (DM&E) Railroad Corp. to serve mines in the PRB region. The ruling may increase rail competition and thus lead to lower delivered prices of PRB coal.

The DM&E project would build about 280 miles of new rail to the Wyoming coal region and upgrade some 600 miles of track in Minnesota and South Dakota. DM&E, based in Sioux Falls, S.D., filed with the U.S. Surface Transportation Board (STB) in 1998 for approval of the project. The developers — including Pittsburgh-based L.B. Foster Co., a maker of rail equipment, which owns about 13% of DM&E — are also seeking some $2 billion in funding for the project from the Federal Railroad Administration. Private-sector investors would then fund the remaining $4 billion.

The STB approved the expansion project in 2002, but the 8th Circuit reversed the board and told the agency to reconsider environmental issues. The board then approved the project again last year after new environmental filings and the appeals court blessed the STB and the lower court ruling.

DM&E hopes to begin construction this year and have coal unit trains on the tracks in 2010. The UP and BNSF have, not surprisingly, opposed the DM&E plan, but it appears likely that the competitive rail line will become a reality. When it begins operating, it will lower the delivered price of low-sulfur coal to an ever-broader geographic market.