TOP PLANTS: Ramagundam Super Thermal Power Station, Karimnagar, Telangana, India

Owner/operator: NTPC Ltd.

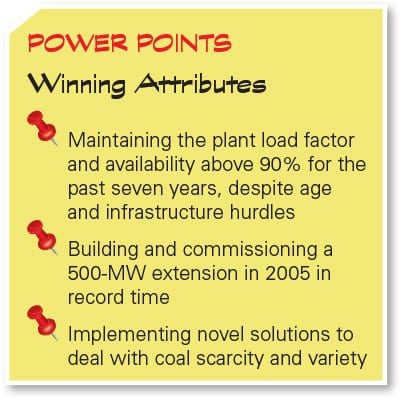

One of NTPC’s first coal-fired facilities, the 2.6-GW Ramagundam plant, is aging well, delivering noteworthy performance metrics that distinguish it from other plants in the state-owned generator’s big coal fleet.

For nearly four decades, the 2.6-GW Ramagundam Super Thermal Power Station’s vermillion-banded stacks have towered over the green teak forests of what is now Telangana state in India’s southern region, their reflection glimmering in the wide Godavari River that snakes nearby. Over the years, politics and economic events have reshaped neighboring regions—lately resulting in the June 2014 split of Andhra Pradesh state, forming India’s youngest state: Telangana. But the plant’s significance has remained monumental. Today, it serves seven states: Along with Telangana and Andhra Pradesh, Tamil Nadu, Karnataka, Puduchery, Kerala, and Goa buy power from the plant.

Meanwhile, from a technology perspective, the plant has become the vanguard of change for the National Thermal Power Corp., Ltd. (NTPC), India’s giant state-owned generator that itself has undergone several transformations over the years. When India’s then-Prime Minister Shri Morarji Desai laid Ramagundam’s foundation stone at the mouth of a coal pit in 1978, NTPC had been incorporated for barely three years. NTPC today owns a 45-GW fleet that provides nearly a quarter of India’s power. About 85% is coal-fired.

Ramagundam consists of seven units: three 200-MW units that were commissioned around 1984 (Ansaldo was the main supplier), three 500-MW units commissioned around 1989, and a new 500-MW unit commissioned in 2005 (Bharat Heavy Electricals Ltd. supplied most of the equipment for the last two stages). As the plant’s Additional General Manager Subrahmanya Srinivas Chamarty told POWER, all seven units were commissioned ahead of schedule—the sixth unit nine months early, and the seventh and final unit more than 11 months early. In fact, Srinivas said, the seventh unit set a national record: It was built in 36 months and 10 days from letter of award placement to synchronization. In 2013, the station took another leap and completed a 10-MW solar photovoltaic (PV) project that reportedly performs at an efficiency level of more than 17% of its plant load factor (Figure 1).

|

| 1. Going solar. The 2.6-GW Ramagundam plant also hosts a 10-MW solar photovoltaic installation built by Lanco Solar Energy. Courtesy: NTPC |

More noteworthy, perhaps, are reports from the station showing marked improvements in performance, even as the plant is aging. The station achieved its best performance 25 years after inception (in 2009–10), and its highest ever availability in 2011–2012, for example. At the same time, the plant load factor and availability have consistently been above 90% over the last seven years.

Asked how operators have managed to achieve this, Srinivas replied, “The simple secret is to manage the maintenance of equipment to achieve always near-design efficiencies and capabilities.”

Over the last 15 years, the plant has accomplished a number of upgrades within noteworthy timeframes. For example, it converted the controls to solid-state distributed digital control monitoring and information systems for the first 500-MW unit in 29 days—much less than the 50 days planned for that task. The same conversion for the 500-MW unit took only 33 days, and a conversion for one of the 200-MW units took 27 days.

|

Grappling with Fuel Uncertainties

Yet another attribute that makes Ramagundam a burnished asset in NTPC’s ever-growing fleet is how it has handled its coal supply to make the most of the ebb and flow of available fuel.

While India is the world’s third-largest producer of coal, it must rely on imported coal to fire its fleet. That irony could be blamed on structural inefficiencies and bureaucratic bottlenecks at every stage of coal exploration, production, transportation, as well as power generation. More troubling for India was that coal imports weren’t growing to narrow domestic shortfalls, owing to inefficient pricing policies that have been made worse over the years by infrastructure constraints. The situation has improved substantially, said Srinivas, but generators must still be resourceful.

Ramagundam was built as a pit-head power plant based on coal availability from the nearby Singareni Mines. Today, it sources coal from seven to eight mines; 70% of its coal comes from local mines, with the balance brought in by rail from other mines 800 km to 1,000 km away. As with other NTPC coal plants, Ramagundam has dealt with coal shortfalls. “As the shortfall from the agreed suppliers is observed, alternate supplies are brought in,” Srinivas explained. “Especially in 2014–15, the station handled its highest-ever coal quantity, including imported coal, since inception of the station.” Planning ahead helped the station avoid generation shortfalls of 2,000 to 2,500 million units during that year, he said.

But relying on so many different coal sources means that coal quality varies continuously. To tackle that, the plant became India’s first to install an online radiometric coal analyzer, a smart device that enables “intelligent” feeding of coal into bunkers, or for blending. The installation will be completed by 2016, Srinivas said. It will help the company maintain a blending/stacking strategy, set an operation regime, and help it plan to comply with environmental parameters.

Environmental Management

The station’s environmental management efforts are also noteworthy. While India currently has no federal standards to curb emissions of sulfur dioxide, nitrogen oxides, and mercury, it has particulate matter standards set by the Central Pollution Control Board.

However, the government is moving to substantially tighten existing particulate standards by 2017, as well as those for other pollutants, and the 30-year-old Ramagundam is already poised to meet proposed standards, said Srinivas. It has been certified to ISO 14001 for its environment management systems, and it features—unusually for an Indian plant—high-efficiency electrostatic precipitators along with tall stacks (225 to 275 meters high). Over the years, it has enabled online monitoring for ambient air quality management systems, opacity meters for stacks, pH meters for effluent monitoring, water flow meters to gauge water consumption, and cameras for ash dyke and chimney monitoring. All these systems are linked to India’s central pollution board as well as to state entities.

The plant also takes pride in its ash management, including maintenance of ash ponds so fugitive emissions are minimized. Notably, it has set up a dry ash extraction and transportation system for extraction of dry fly ash as well as commissioned a rail-loading system to help utilize all of its fly ash. It currently supplies about 60% to 80% of its fly ash to nearby industries for making cement, mine fill, and bricks.

A Brighter Future

These improvements to boost performance, improve safety, and protect the environment have been recognized a dozen times through accolades awarded by the government of India, state governments, and other entities, including the British Council and the Institute of Engineers. For its stellar performance despite age and infrastructure hurdles, it has now also earned a Top Plant Award from POWER.

But the plant’s upgrades aren’t completed yet, Srinivas noted. Plans are in effect to expand the station by 4 GW. That will entail building two 800-MW units in the first phase, which already has public backing, and three 800-MW units in a second phase. Ramagundam may, meanwhile, become the site of a 15-MW solar PV extension if plans fall into place. ■

—Sonal Patel is a POWER associate editor.