Norway Setting Strategy for Offshore Wind

Offshore wind is big business in the North Sea, with dozens of wind power installations commissioned in the region over the past two decades. Norway, a country that gets 98% of its power from renewable energy, primarily hydropower, in February announced plans for its first auction for offshore wind. The tender, scheduled in the second half of this year, at first would look for bids to develop at least 1.5 GW of offshore wind capacity to supply the country, with subsequent tenders designed to provide an economic boost by providing more electricity for export to Europe. Several companies already are lining up to participate in Norway’s effort, looking to expand their own offshore wind ambitions and showcase new technology that draws on some groups’ experience with the oil and gas exploration industry.

Shell and BP are among the companies with interest in the Norwegian installations, along with Eni, Equinor, and Orsted. Vattenfall and Norway’s Seagust also said they have formed a joint venture to bid in the auction; EDF Renewables in December said it had partnered with Deep Wind Offshore, a Norwegian independent power producer, to participate in the process.

|

|

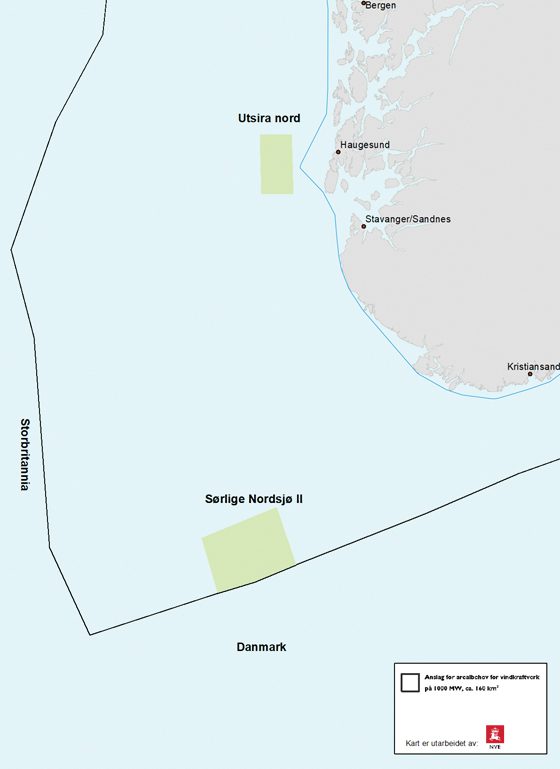

1. Norway’s government has identified two areas in the North Sea—Utsira Nord and Sørlige Nordsjø II—for offshore wind development. Courtesy: Norwegian Ministry of Petroleum and Energy |

Norway’s government had earlier identified two North Sea areas (Figure 1)—Utsira Nord and Sørlige Nordsjø II—for development of as much as 4.5 GW of fixed-bottom and floating offshore wind, and immediately gained interest from both domestic and international investors. Sørlige Nordsjø II will house two or three fixed-bottom wind farms, while Utsira Nord could have three 500-MW sites for floating turbines, according to the Norwegian Ministry of Petroleum and Energy. Government officials said the two sites will be tendered as separate processes with different timelines and tender rules.

Public support in Norway for offshore wind has been mixed, as the question of exporting power to the rest of Europe is controversial due to the potential impact on power prices. The government, after announcing its auction plans, also said the first Norwegian offshore wind farms built in the North Sea would not be allowed to connect to foreign markets, and could only send power to Norway—which could impact the investment interest of some companies, including Equinor, which said it was counting on hybrid connections from offshore installations that could serve multiple countries.

The recent announcement marks Norway’s first tender for bottom-fixed offshore wind turbines in the southern North Sea. Prime Minister Jonas Gahr Stoere in February said the first turbines could be installed within a few years, and said the government expects to subsidize the project to at least get it started, in part due to concerns about limited outside investment if the first builds only serve Norway. Stoere said a second development phase, with the same capacity and in the same area of the southern North Sea, will come later, and would likely be allowed to supply energy to the European continent as well as Norway—a critical component, according to a financial adviser who spoke with POWER.

“It would be criminal for Norway to miss the offshore wind market growth in Europe. The country’s economic growth has long been tied to energy, and offshore Norway is a world-class wind resource, on par with the Norwegian oil and gas resource in scale and quality,” said Neal Dikeman, co-founder and partner at Energy Transition Ventures, a Houston, Texas–based venture capital fund manager. “Notwithstanding the technical and cost issues, the key to offshore wind in Norway actually becoming a world-class energy resource will be two things: massive volume reducing the cost of floating wind, as most of the best Norwegian resource is in water too deep for fixed wind platforms, and development of T&D [transmission and distribution] infrastructure tied into European power grid and markets. Quite frankly, viability of offshore wind often hinges on ease of project development, and how much T&D infrastructure is needed, and development issues for that T&D.”

|

|

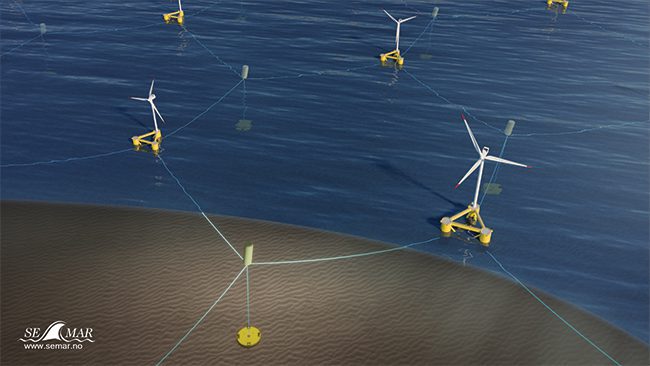

2. Honeymooring is a unique and cost-effective way of mooring floating wind turbines in a “honeycomb” network using special equipment, flexible lines, and shared anchors. Honeymooring is estimated to reduce mooring hardware costs by 50% compared to traditional mooring solutions with chains and clump weights. Courtesy: Semar |

Connections to the European continent that would drive more investment are also seen as important for other technological advancements. TotalEnergies, a French company with a long history in oil and gas that has transitioned into renewable energy, is another group interested in Norway’s offshore wind program, with plans to deploy advanced technology. TotalEnergies recently said it had selected Norway-based Semar’s Honeymooring solution (Figure 2) for its offshore wind projects, which it said was expected to reduce development costs of TotalEnergies’ future offshore wind developments not just in Norway but worldwide.

Floating wind turbines have removed depth constraints from offshore projects, but do bring a design challenge related to reliable and cost-effective mooring. The Honeymooring technology connects floating wind turbines in a “honeycomb” network, using established mooring technology from the oil and gas industry to create what Semar calls a “more effective anchor-sharing configuration.”

“Thanks to our longstanding experience in the offshore oil and gas industry, we know mooring systems very well, and as we today have a large portfolio of offshore wind projects, we are proud to partner with Semar in the development of the innovative Honeymooring solution, which will contribute to lower the cost and the environmental impact of offshore wind energy,” Olivier Terneaud, vice president of Offshore Wind at TotalEnergies, said in a statement. Thor Valsø-Jørgensen, CEO of Semar, said, “We are proud to have TotalEnergies as one of the important partners and contributors in the development of the Honeymooring solution. The overall project is being lifted by their support and the high-quality expertise which contribute to keep all of us in the forefront of the transformation towards green energy for the future.”

|

|

3. In the spring of 2021, 11 substructures for the Hywind Tampen floating wind farm were transported from the Aker Solutions yard at Stord, Norway, where the first 20 meters were built, to the deep-water site at Dommersnes, Norway, where the slip-forming work was to be continued to 107.5 meters. The completed wind turbines are scheduled to be towed to Tampen in early summer 2022 and offshore work is expected to be finished by the end of the year. Courtesy: Equinor / Lars Melkevik – Aker Solutions |

Norway’s Ministry of Petroleum and Energy last summer acknowledged “there is a big difference in the levels of maturity between bottom-fixed offshore wind technologies and floating wind. The government believes that support for technology development is the most appropriate tool for developing floating offshore wind solutions in Norway, as demonstration projects may help to reduce costs.” The government has supported Norway-based Equinor’s role in advanced offshore wind technology; Equinor expects to bring the 88-MW Hywind Tampen (Figure 3), the world’s first floating wind farm to power an offshore oil and gas platform, online this year. The project will provide electricity for the Snorre and Gullfaks offshore field in the North Sea.

Norwegian officials have talked for years about advancements in electricity transmission, including the long-discussed North Sea Super Grid that could provide high-voltage direct current (HVDC) connections among several offshore wind farms and onshore grids. “For over a decade Norway and other countries have been talking about a high-voltage DC meshed super infrastructure grid in North Sea to bring wind power from its best resource to Europe,” said Dikeman. “This was always a great idea. While some infrastructure has been laid, the North Sea HVDC Super Grid has remained largely talk. In that same time frame Russia got Nord Stream 2 to Germany built. Norway should be pulling out all the stops to do the equivalent for subsea wind transmission.”

In addition to holding auctions for the rights to build in the Utsira Nord and Sørlige Nordsjø II, the Ministry of Petroleum and Energy said it would commission the Norwegian Water Resources and Energy Directorate (NVE) to identify new areas for offshore wind development, including preparing an impact assessment program over the next year. Dikeman said the country should build transmission infrastructure now, though, and not wait for projects to be developed.

“Norway would be best served by simply putting in place the T&D infrastructure needed to supply Europe with wind power now, without waiting for projects, and simultaneously clearing the road for development restrictions on its offshore floating wind developments,” he said. “Like the oil and gas pipelines, whoever gets the T&D infrastructure in first in the best route to market, and streamlines upstream development, wins the race.”

—Darrell Proctor is a senior associate editor for POWER (@POWERmagazine).