India's Coal Glut Leaves Producers Teetering on Bankruptcy

At the end of July, India’s Central Electricity Authority (CEA) noted in its annual load generation balance report (LGBR) for the year 2018–2019 that the country will likely have a peak surplus of 2.5% and an energy surplus of 4.6%, varying by state. That’s a stunning turnaround for a country that recorded a peak deficit of 12% and an energy deficit of 11% only a decade ago—a period during which its population surged by about 130 million to the present 1.32 billion people. The country accomplished that armed with an ambitious plan to dramatically double its capacity and resolve chronic power shortages, which it recognized were detrimental to long-term economic growth. The feat required embarking on a series of reforms and pushing for rural electrification.

But capacity growth appears to have changed unevenly by the massive build-out of coal-fired power plants. Since 2012, India has added a total of 85 GW of new coal capacity—far exceeding targets set out in the 12th Five-Year Plan (2012–2017) for 69 GW of coal and 520 MW of lignite. During that time, it also added 5 GW of hydro, 7 GW of gas, and 2 GW of nuclear capacity. As of March 2018, according to the Ministry of Power, the country had 343 GW of total installed capacity, 57.3% of which was coal-fired; 7.2%, gas-fired; 0.2%, oil-fired; 13.2% hydro; 2%, nuclear; and 20.1% renewables, including wind and solar.

In the next national electricity plan (2017–2022), India wants to add even more capacity, including 175 GW of renewables, which should serve as adequate replacement for 22 GW of older, inefficient coal capacity that is expected to retire. Meanwhile, the ministry underscored that 6.4 GW of new coal capacity will be needed to meet peak demand—but it noted that about 47.9 GW of coal capacity, already in various stages of construction, is likely to be commissioned over the next five years.

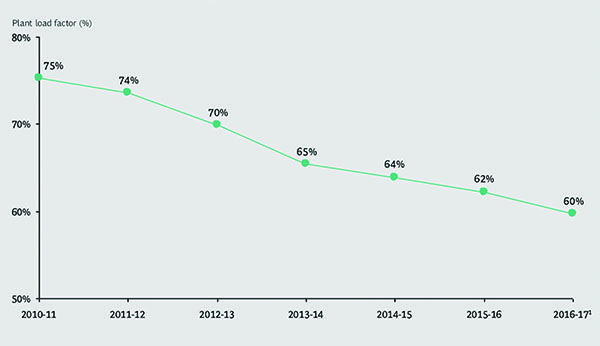

India is also acutely aware that its existing coal fleet is underutilized, and notes that over the past five years, the national average plant load factor (PLF) for India’s coal and lignite plants—a measure of average capacity utilization—began a downward tumble (Figure 3). Whereas in 2008–2009, average coal unit PLF was 77.2%, in 2017–2018, it fell to 59.9%—a historic low. (PLF for gas generation fell even more precipitously, from 60% in 2008–2009 to 22% in 2016–2017, owing to limited availability of gas.) The Power Ministry expects that by 2021–2022, coal unit PLF could fall to 56.5%.

|

| 3. A coal reality. Coal plant load factors in India have dropped significantly over the years, owing to a number of factors. Source: India’s Central Electricity Authority |

The news is distressing for India’s coal generators, who industry experts say are facing a serious three-pronged assault. In a recent report, the industry-led and managed Confederation of Indian Industry (CII) said that as energy demand fails to keep pace with the rise in supply, the poor financial health of state distribution companies (DISCOMs) have hampered them from committing to long-term power purchase agreements (PPAs).

Most are burdened by debt overhangs, which have only grown since 2011, owing to insufficient tariff hikes and subsidies. Between 2012 and 2016 only 14 GW of PPAs were announced for new coal plants, CII said. Without PPAs, independent power producers (IPPs) are exposed to volatile prices in the short-term market, it said. Adding to these woes, coal generation must directly compete with government-imposed renewable obligations, further burdening DISCOMs and discouraging investment in conventional generation.

Industry must also grapple with real and widespread fuel supply risks, owing to the government’s monopoly on coal supply through Coal India. Private players are especially vulnerable because they cannot receive letters of assurance for coal allocation without PPAs. Domestic coal prices have also been increasing year-on-year over the past six years, and already financially strapped generators must pass on that cost to consumers, the CII noted.

Yet another issue assailing generators is the exorbitant cost of freight, which constitutes 20% to 30% of fuel costs for thermal plants—which are typically sited away from coal sources. “Freight charges in India are among the highest in the world,” and they have increased by nearly 50% over the last five years alone. Sea freight, on the other hand, has fallen by the same amount, CII said, as it called for reforms to the rail-freight network, including re-allocations, enhancing labor productivity, and pricing optimization. At the same time, coal generators are dealing with “a gap” in the coal invoiced and the coal received, slippage which typically occurs on an order of one to two grades, depending on the mine.

Finally, compounding supply and demand challenges faced by coal generators, a large number of projects experience execution challenges, which inevitably result in delays and cost overruns. Land acquisitions lead the list of those concerns, CII said, but it also pointed to IPP financial hiccups.

In a report published in March 2018, India’s Parliamentary Standing Committee on Energy recognized the severity of the industry’s troubles. The government acknowledged 34 coal-based thermal power plants can be categorized as “financially stressed,” which means a stunning 40.1 GW of coal-fired power projects are stranded—and 15.7 GW isn’t even yet commissioned. Of the 34 projects, 17 (15.2 GW) were affected by a lack of coal linkages. Analysts peg the companies’ outstanding debt at 1.75 trillion rupees ($25 billion), which could cripple banks if they default.

But according to Tim Buckley, director of energy finance studies for Australasia at the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA), and IEEFA research associate Kashish Shah, the problem may be much bigger. Coal sector lenders are trying to restructure and resolve some $40 billion in stranded assets, they said in August.

The sector’s woes reflect a “combination of excessive financial leverage, operational inefficiencies and competition arising from accelerated deflation in renewable energy tariffs, all of which make investors [skeptical] of the sector.” And these concerns likely won’t be alleviated soon: “As per India’s [CEA] estimates, the tariff for a new emission controls compliant pit-head supercritical coal-fired power plant should be Rs 4.39/kWh (for a PLF of 60%). With super competitive renewable energy PPAs with zero indexation now regularly priced in the Rs 2.50–3.00/kWh range, new coal power plants are struggling for viability across India,” they said.

In light of these developments, a number of coal plant developers have decided to abandon projects. This June, NTPC shelved the 4-GW greenfield Pudimadaka Ultra Mega Power Project, which had a PPA with the government of Andhra Pradesh but failed to obtain a domestic coal linkage. In July, the company also dropped the 2-GW Nabinagar 2 in Bihar and 1.6-GW Katwa units in West Bengal, though they had PPAs with multiple states. NTPC, which has 47 GW of existing coal generation, has shelved 10.5 GW since February 2018, Buckley and Shah noted. That’s in line with projections made in July by the Global Coal Plant Tracker that suggest 573 GW of coal plants in India have been canceled between 2010 and June 2018. “Projects vanishing from company documents is another sign of companies quietly walking away from the projects,” they noted.

—Sonal Patel is a POWER associate editor.