Feds and States Join Forces to Push CHP

Courtesy: Bilfinger Berger Group

Combined heat and power (CHP), also known as cogeneration, has long been a niche generation resource in the U.S., largely confined to industries needing a reliable source of steam and institutions like hospitals and universities needing uninterrupted power and heating. Though a few housing cooperatives, mostly on the East Coast, make use of CHP for both power and district heating, it has remained an “under the radar screen” option for the public.

But if the Obama administration and some forward-thinking states get their way, that may be about to change.

At the end of August, President Obama signed an executive order calling for an expanded role for CHP in the national energy mix. In it, he set a goal of deploying 40 GW of new CHP capacity by 2020, which would double the current installed base.

The directive does not order the private sector to install anything; rather, it instructs the Departments of Energy, Commerce, and Agriculture, and the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), in coordination with several other agencies, to convene a series of public workshops to address the barriers to CHP deployment, and to encourage investment in CHP by:

- Providing assistance to states on accounting for the potential emission reduction benefits of CHP.

- Providing incentives such as set-asides under emissions allowance trading program state implementation plans, grants, and loans.

- Employing output-based approaches as compliance options.

- Utilizing existing partnership programs to support energy efficiency and CHP.

- Providing guidance, analysis, and information on the value of CHP to states, utilities, and owners and operators of industrial facilities.

- Improving the usefulness of federal data collection and analysis.

- Assisting states in developing and implementing specific best practice policies that promote CHP.

The order also notes that “these agencies should consult with the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, as appropriate.”

Concurrent with the order, the EPA released a 22-page report touting the benefits of CHP as a “clean energy solution.” Among other things, the report estimates that the technical potential (that is, not considering the economics) for additional CHP at existing industrial facilities is just under 65 GW, with the corresponding technical potential for CHP at commercial and institutional facilities at just over 65 GW, for a total of about 130 GW.

How much of this unexploited potential is economically viable depends a great deal on the future direction of natural gas prices, but the figures suggest that the president’s 40-GW goal is achievable, if ambitious.

The EPA’s Combined Heat and Power partnership, formed in 2001, was set up to support the development of CHP nationwide. It currently consists of more than 450 members, but thus far has had fairly minimal impact. The EPA reports having facilitated more than 600 CHP projects, amounting to just under 6 GW in total capacity. (For comparison, total natural gas capacity additions over the same period, according to the Energy Information Administration, have been more than 200 GW.) It is likely, though, that the partnership will play a key role as the EPA is called upon to implement the president’s directive.

State Initiatives

CHP is also gathering steam, so to speak, at the state level. Several initiatives are worth mention.

California. In 2010, Governor Jerry Brown set a goal of adding 6,500 MW of CHP to the California grid by 2020. The state has also established a feed-in tariff for CHP systems under 20 MW with excess power that meet certain criteria for efficiency and design, an initiative that is already fostering some innovative uses for CHP.

The state currently has about 8,500 MW of installed CHP capacity; about 30% is used in on-site applications, and 70% is exported to the grid (Figure 1). In September, the California Department of Energy issued a policy paper laying out a detailed path for reaching Brown’s target through changes in policy and regulation.

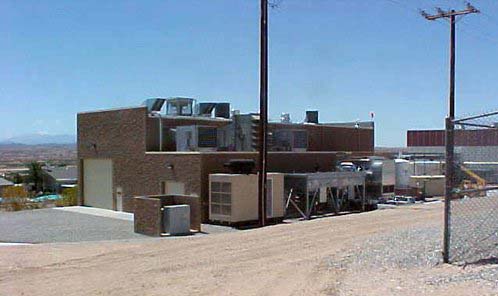

1. This 7-MW CHP system is part of a comprehensive set of energy and facility upgrades at the Marine Corps Air Ground Combat Center in Twentynine Palms, California. Source: NREL

It also pointedly recognizes that the state’s new cap-and-trade regime is actually a disincentive to install a CHP system, because in its current form, the system owner has to compete with the grid as a whole. What needs to change, the paper suggests, is that “CHP should be incorporated into the RPS calculation, allowing all electricity generated, on-site or exported, to be compared to the utility’s marginal, or least efficient, generator.”

Massachusetts. The state’s 2008 Green Communities Act includes a rebate incentive for efficient CHP systems. The incentive is determined by considering the value of CHP in the utility’s overall energy efficiency portfolio, the project’s cost-to-benefit ratio and contribution to energy efficiency, and customer investment threshold. All of the power generated via CHP is credited to the utility’s energy efficiency goals. The state also provides direct grants for CHP for municipalities that meet certain eligibility criteria.

New York. The state’s Energy Smart New Construction Program provides cash rebates and technical assistance for CHP systems, in new or substantially renovated buildings. The state also offers a smaller scale program for existing facilities.

Several other states offer low-interest loans or tax credits for CHP. Of the 33 states with renewable portfolio standards, 23 include CHP in one form or another.

It’s too soon to tell how much traction these incentives can develop for CHP. Still, with projections for continued low gas prices, combined with expiration of the Production Tax Credit that will reduce support for some renewables, the CHP industry could be poised for significant capacity additions in the next few years.

—Thomas W. Overton, JD is POWER’s gas technology editor. Follow Tom on Twitter @thomas_overton.