Whistling in the dark: Inside South Africa’s power crisis

State-owned Eskom has a near-monopoly on power generation in South Africa. Though one might think government control would make the business of managing power supplies easier, the story of Eskom’s recent troubles shows that state ownership, in and of itself, is neither the problem nor the solution. More important than ownership structure are policy and planning decisions that take the long view. Eskom’s cautionary tale should remind those involved in the power industry anywhere in the world that — to vary a disclosure from the financial sector that too few have paid attention to — past performance is not a guarantee of future success.

January 25, 2008 — Black Friday, as South Africans know it — wasn’t the beginning. For three months straight before that summer day, the nation peopled by 47.9 million had seen widespread rolling blackouts that would plunge whole towns into darkness for as long as eight hours at a time.

Only that week, scores of tourists had been trapped midway in cable cars to and from Cape Town’s Table Mountain. And the day before, Eskom, the state-owned utility and supplier of 95% of the nation’s power, had been faced with an alarmingly low reserve margin.

In its effort to bridge the growing disconnect between demand and supply that had stretched to a staggering 4,000 MW, and to prevent a collapse of the national grid, the utility called for the worst round of load shedding South Africans had ever seen.

In desperation, Eskom declared force majeure on Jan. 25, requesting that key industrial customers implement a 10% load reduction to prevent a grid collapse. At the same time, the South African government — led by Eskom’s overseers, the Departments of Minerals and Energy (DME) and Public Enterprises (DPE) — declared a "national electricity emergency." South Africa — a country that the World Bank ranked 24th in terms of gross domestic product (GDP) in 2007, the torchbearer for all Africa — was in its darkest hour.

Some of the largest metal producers in the world — Anglo Gold Ashanti, Gold Fields, and Harmony — immediately halted operations and stayed shut for five days, claiming safety considerations. In the first quarter of this year, the country’s prized mining sector — which uses 15% of Eskom’s power — experienced a 22.1% contraction in output.

The domino effect was widespread: The plunge in industrial output sent prices of gold and platinum soaring worldwide, and with the number of exports reduced, the rand devalued. This in turn dragged down the country’s industrial and manufacturing sector, already hard hit as it consumes 38% of Eskom’s power.

Despite the government’s urgent pleas to reduce demand, and power prices that have already risen nearly 30% this year, former Public Enterprises Minister Alec Erwin admitted in September, a mere eight months after Black Friday, that consumption had decreased only 4% — far from the 10% needed to avoid a new round of widespread power cuts. And, as the National Energy Regulator of South Africa (NERSA) would later tell the nation, the damage to the economy was serious: In concrete figures, from November 2007 to January 2008, the nation had suffered a loss of 50 billion rand (US$6.07 billion). The country’s GDP growth had fallen to its lowest rate in more than six years.

By February 2008, Eskom-bashing had become a national pastime. And there was no light at the end of the tunnel. "We are going to be in this [crisis] for years," Eskom CEO Jacob Maroga had then said. "The threat of load-shedding is with us for some time."

Descending into darkness

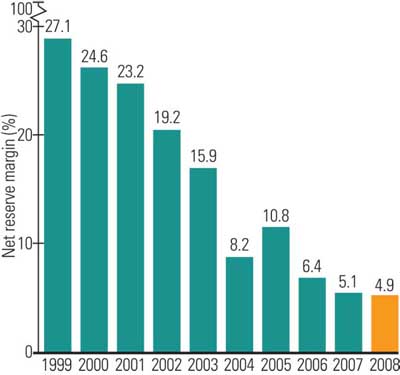

How did things for a utility with a net generating capacity of 38,744 MW — the 13th largest in the world — deteriorate so quickly? A mere decade ago, this monolithic monopoly had excess capacity with a reserve margin of more than 25% (Figure 1) — an impressive figure, considering it supplied (and still does, according to claims on its web site) a stunning 45% of Africa’s total electricity (see sidebar, "An African powerhouse").

1. Fraying around the edges. South Africa’s net reserve margin has been steadily declining since 1999 as a result of increasing demand and lack of additional capacity being commissioned. In 2008 the reserve margin reached alarmingly low levels, forcing Eskom to implement extensive load-shedding measures to prevent partial or complete blackouts. (Note: Percentages are for winter peak.) Courtesy: Eskom

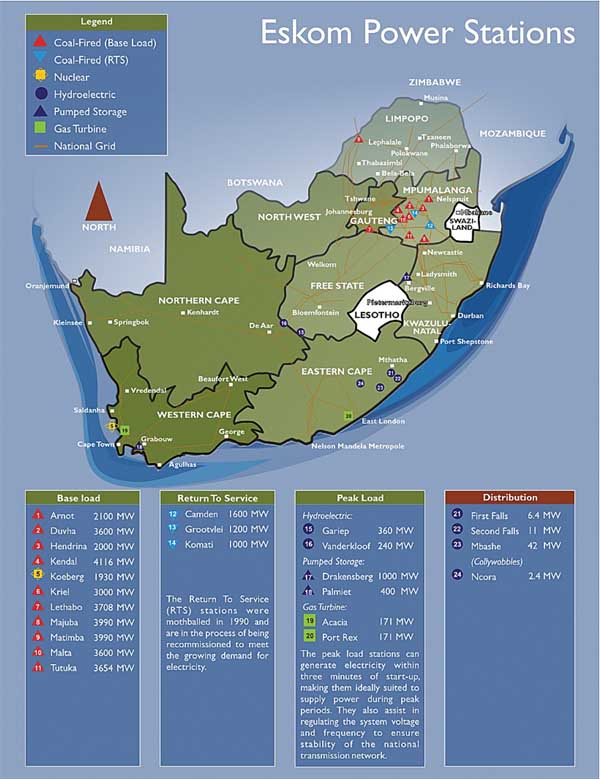

Thanks to giant coal-fired installations like the 4,116-MW Kendal Power Station (Figure 2), the electricity it sold — even if incorrectly priced, as Eskom has long argued — was the cheapest in the world, making the company popular among foreign investors and South Africans alike. For many years the government, too, treasured the utility, branding it the crown jewel of South African state-owned enterprises. And it was internationally renowned, winning several awards and honors, the most recent of which was the Financial Times Global Energy Award for Power Company of the Year in 2001.

2. African king. Since its sixth unit began operations in 1993, Eskom’s 4,116-MW Kendal Power Station stands (in terms of installed capacity) among the world’s largest coal power plants. In South Africa’s Mpumalanga province (see Figure 3), it is clustered with three mothballed (but soon-to-be-revived) plants and nine currently operating coal plants. Several are of a similar size, such as the 3,990-MW Majuba plant. Courtesy: Eskom

"With all the accolades, it was exceedingly difficult for Eskom to convince anyone that the organisation was on an unsustainable path," says Valli Moosa in the utility’s 2008 Annual Report. Moosa, an Eskom chair, recently stepped down, having completed a three-year tenure that started in 2005. "Within Eskom, however, the mood was completely different. There was a sense of urgency and anxiety to act — and act decisively. It was almost as if Eskom had a premonition that there was an electricity crisis looming, which had to be averted."

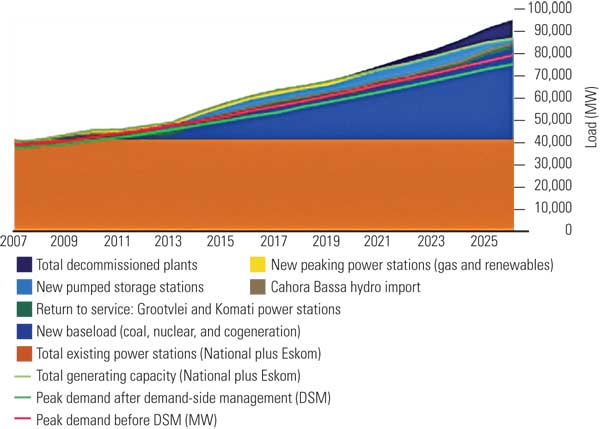

That "premonition" was in large part based on a single point Eskom’s management had been voicing for over a decade: If the South African economy were to grow at the government target of 6%, demand on the grid would increase by about 1,600 MW per year.

In 1998, the utility’s concerns were finally published in a white paper on energy policy from the Department of Minerals and Energy. The admonition was clear: "Eskom’s latest Integrated Electricity Plan forecasts for an assumed demand growth of 4,2% that Eskom’s present generation capacity surplus will be fully utilised by about 2007." It added emphatically, "Timely steps will have to be taken to ensure that demand does not exceed available supply capacity and that appropriate strategies, including those with long lead times, are implemented in time. The next decision on supply-side investments will probably have to be taken by the end of 1999 to ensure that the electricity needs of the next decade are met."

But in 2000 and 2001, when key government officials and regulators met with Eskom to revamp the electricity supply industry in accordance with the white paper, these warnings were virtually ignored.

"To be fair, the then new [post-apartheid] government a decade ago was grappling with an array of what must have seemed more important public policy interventions," said Member of Parliament and Zulu leader Prince Mangosuthu Buthelezi in an open letter to the nation in January 2008. "It is understandable, if not excusable, that the policymakers’ radar missed the early warning."

South African media reports describe the high-ranking officials who attended these meetings — and ultimately made the decision to block Eskom from constructing new capacity — as "flushed" from a second African National Congress (ANC) electoral win in 1999. Now they were looking to match their political triumph with economic achievements. Of particular priority was connecting hundreds of black townships — millions of new users — to the grid.

At the same time, the group was preoccupied with restructuring state assets — starting with Eskom, which was to be stripped of its monopoly and unbundled into three different operating entities: generation, transmission, and distribution. The government’s plan was to have 30% of the nation’s power generation provided by independent power producers (IPPs). Eskom, which would be turned into a dividend- and tax-paying corporate citizen, would take care of the remaining 70%.

The government figured that IPPs would rush at the opportunity to build new projects if Eskom were barred from them.

But IPPs did not materialize — and Eskom had almost expected they’d be no-shows. "Based on the fact that South Africa ranks amongst the cheapest electricity providers in the world, the subsequent cost-benefit analysis and rate of return estimates in the calculation of the real cost of electricity meant that IPPs were unable to competitively provide power," a utility analysis of the crisis reveals.

Then the 2001 California electricity crisis happened, making a worst-case scenario more conceivable. As Eskom saw it, South Africa’s power market was etched with hallmarks similar to California’s. It suffered the same lack of investment in the generation, transmission, and distribution systems and the same lack of financial incentives to encourage new power producers that were the factors then held responsible for the California crisis. Working closely with a California power producer, the utility even compiled and presented a brief on the matter to the government — but, again, with no success.

Growth but no capacity development

South Africa’s power generation sector had certainly seen better times. In the 1970s, the U.S. and European countries were willing to do business with the pariah state. But, after former president P.W. Botha’s infamous "Rubicon speech" in 1985 — in which he essentially refused to consider apartheid policy reforms and shunned hostile pressure and agitation from abroad — the country’s economic growth dwindled from 4% to 0% virtually overnight. All industries were affected — including the power sector. Eskom’s investments in new capacity grew stale, and several plants were shelved to balance the diminished demand and excess supply.

Since 1994, finally relieved of foreign economic sanctions, the country has experienced robust economic growth. Because the nation’s electricity was the cheapest in the world, foreign companies from highly energy-intensive sectors invested heavily in South Africa. Added to this, by 2008, government subsidies had connected the masses to the grid. Demand for electricity surged. Eskom’s Maroga estimates that post-apartheid growth was about 50%.

"This welcomed growth has all but exhausted Eskom’s surplus electricity generation capacity. To us at Eskom, this has been one indicator that we watched closely and with a sense of trepidation. Monitoring the diminishing reserve margin has been an integral part of Eskom’s operations, as it is a proxy for the long-term adequacy of the power system, including the short-term security of supply," the CEO says in the 2008 Annual Report. "In the absence of any investment in new generation capacity, misalignment between the demand and the available supply emerged and therefore the 2007 crunch was inevitable."

The utility didn’t exactly sit back and wait, though. "We started preparing for [an uncertain] future, refocusing Eskom’s strategy away from an African-wide, diversified, unbundled business model to one which focused on the core business of power generation, transmission and distribution, with a focus on South Africa’s market," says Moosa.

Adding capacity with its hands tied

Between 2001 and 2004, Eskom poured its resources into a program to increase capacity. Without official mandate, it began work on the 1,332-MW Braamhoek (now called Ingula) pumped storage facility (Figure 4), a 13-year-long project, telling the government it would sell it to an IPP, as needed, later.

4. Eskom’s scheme. The 1,352-MW Ingula is a giant pumped-storage project that Eskom began building early this decade near Ladysmith, KwaZulu-Natal, while the cabinet had imposed a ban on construction of new projects. It will comprise two dams—one at the top and the other at the bottom of the escarpment—and underground waterways, an underground powerhouse complex, access tunnels, and access roads. Water will be pumped up to the upper dam at times of low electricity demand and released at times of peak electricity demand to generate electricity via hydroelectric turbines. All four units will be commissioned in 2013. Courtesy: Eskom

It also began a program to return to service three mothballed coal-fired stations — Camden, Komati, and Grootvlei — hoping they would restart between 2002 and 2006. But, with the plants in bad shape and budgets to fix them ballooning, Eskom was forced to extend timelines. Finally, in March 2005, Unit 6 of the eight-unit 1,620-MW Camden station was successfully synchronized to the grid and began producing electricity for the first time in 15 years. Since then, six of the eight units have entered commercial operations, and the entire station will have returned to service later this year (Figure 5). In the meantime, Eskom plans for the 1,200-MW Grootvlei power station to return to service by March 2009, while the 1,000-MW Komati power station is scheduled to be in commercial operation by 2010.

5. Rekindling an old flame. Eskom’s coal-fired Camden station was first commissioned in 1967. Following a period of excess capacity, all eight units of the 1,620-MW station were mothballed in 1990. Fifteen years later, in March 2005, Unit 6 was revived to help Eskom increase supply levels and potentially avert a power crisis. Since then, six of the eight units have entered commercial operation. Eskom believes that the entire station will be successfully returned to service later this year. Courtesy: Eskom

The rough road to recovery

Only in October 2004, after a leadership change occurred at the Department of Public Enterprises, did the government lift its construction ban on Eskom. According to Moosa, Eskom immediately moved to address six critical challenges: keeping the lights burning on the back of inadequate reserve margin; addressing artificially low tariffs; building new generation and transmission capacity to meet rising demand; mobilizing South Africans to become more energy efficient; responding to climate change imperatives; and mobilizing all three spheres of the government.

In short, it embarked on a damage-control mission.

Immediately, the pace of building new capacity quickened. Toward the end of 2005, the utility’s board approved an investment to build democratic South Africa’s first two new power stations — Gourikwa (444 MW) and Ankerlig (592 MW) open-cycle gas turbine (OCGT) stations (Figure 6).

6. Raise the anchor. On June 25, 2007, the Ankerlig and Gourikwa open-cycle gas turbine stations—the first new power plants built in South Africa’s post-apartheid era—began operations. Located north of Cape Town, the Ankerlig (shown here) consists of four units rated at 148 MW each. Eskom is currently constructing an additional five 150-MW units. The plant’s name comes from an Afrikaans phrase meaning “lift the anchor,” which is symbolic for a community that rises above the chains of poverty to experience growth and prosperity. Courtesy: Eskom

"The last time Eskom built and commissioned an OCGT plant was in 1976, and so the utility started this project having lost all of its institutional memory in this regard," recalled Moosa. Nevertheless, construction at both sites started in January 2006. The total duration of the project from concept to completion was two years and nine months, with construction taking a meager 17 months. The plants were ready to supply power for the winter of 2007. "This is world class performance by any measure," Moosa added.

The burden borne for the load shed

In December 2007, amid the handwringing and blame game, South African President Thabo Mbeki — who recently left office amid demands for his resignation — admitted the government’s indecision and paralysis was a root cause of the crisis. "When Eskom said to the government, ‘We think we must invest more in terms of electricity generation,’ we said, ‘no, but all you will be doing is just to build excess capacity,’ " he recalled at an ANC fundraising dinner. "We said, ‘not now, later.’ We were wrong. Eskom was right. We were wrong."

But it is not true that Eskom was a passive victim of the government’s decisions, say executives from the South African Centre for Development and Enterprise (CDE). At that group’s July roundtable discussion, senior government, and trade and business leaders remarked that the utility made poor decisions that exacerbated the crisis. "It placed a much higher value on racial transformation and affirmative action than on finding and keeping the skills it needed to manage and maintain its operations. It also made the wrong choices about coal contracting."

According to NERSA, despite the system operator’s extensive use of available emergency resources, such as demand market participation and emergency generation, five load-shedding incidents occurred in November, four in December, and a staggering 14 in January. The ones in November and December arose from general generation capacity shortages.

But in January, by Eskom’s own admission, the situation was exacerbated by technical faults to units that had to bear the burden of others taken off-line for planned maintenance. Worse still, unusually heavy rains during January and February 2008 reduced the coal to sludge. This caused production delays at collieries and coal-handling problems at power stations. Added to this, the quality of coal received was poor, which forced the utility to burn increased fuel volumes to generate needed power (see sidebar, "Looking forward").

Addressing skills and performance inadequacies

Workforce issues have also beset Eskom, though the utility has continued to deny that its current problems are due to a shortage of skills. In 1995 the utility employed almost 40,000 people. By 2007 that number had fallen to 30,746.

By March 2008, in the midst of a massive national and international recruitment effort to plug the skills gap for its capital expansion program, the utility had a staff of 32,954. As of July, a team of more than 2,500 engineering, project management, and commercial resources — supplemented by 19 local and foreign engineering and project management companies contracted as partners over the next five to 10 years — was actively involved in the execution of the building program.

Also in 2008, however, Eskom’s turnover increased to 6.9% — 1% higher than the year before. The utility estimates that "2,958 additional core, critical and scarce skills need to be recruited or developed" cumulatively over the next five years to replace losses and cater to Eskom’s new construction program. The task will be challenging, it admits, given that utilities around the world are experiencing a skills shortage.

The cracks in the utility’s organization had already begun to show between November 2005 and March 2006, when six crippling blackouts hit the Western Cape region. These had been attributed to a number of malfunctions at Eskom’s Koeberg nuclear power plant (Figure 8).

8. African queen. Eskom’s 1,800-MW Koeberg nuclear power station on South Africa’s western coast is Africa’s only nuclear power plant. According to federal regulators, Eskom’s negligence and poor maintenance of the plant caused rolling blackouts that hit the Western Cape region in late 2005 and into 2006. Eskom disputed those findings. Courtesy: Eskom

NERSA had then released a damning report that found Eskom guilty of negligence, poor maintenance, inadequate protection systems, and breaching its license conditions at the plant. According to NERSA — though Eskom disputed these findings — the incidents ranged from a leaking tank that went unreported for months, a missing wire, and a "crow that flew a piece of wire into the tower to build a nest."

Likewise, at times in January and February 2008, 25% of Eskom’s capacity was simply unavailable due to planned and unplanned events. "The current fleet of power stations is not equipped to run continuously at high load factors due to a limitation on the support of auxiliary systems that only permit a certain load factor," the utility says. This, combined with the fact that the plants are in "mid-life" and require above-average levels of maintenance, added to the challenge of keeping up capacity levels.

And the problem continues: In April 2008, Eskom’s chief generation officer, Brian Dames, told Engineering News that he was "very worried" about the state of the utility’s power plants, specifically about the condition of boilers, electrical power generators, transformers, and coal-handling plants. Dames said the next round of load shedding (which lasted from April 1 to May 1) would give the utility a little time to perform maintenance tasks.

Short-term damage control

When it became apparent on Jan. 25 that widespread demand-curbing measures (in addition to load shedding) would be required to secure the power system’s stability, Eskom, the DME, and the DPE declared a national electricity emergency and mobilized a three-phase response plan.

The first phase lasted until Feb. 29 and focused on achieving a 4,000-MW reduction (3,000 MW by users and 1,000 MW by Eskom itself) through a power conservation program based on a model that Brazil adopted during its energy crisis in 2001. In its most basic form, that scheme penalized users who exceeded their allocated quota and incentivized users who used less than their quota, which was set by usage class. Energy efficiency was promoted through programs that included 20% to 30% subsidies for solar water heaters.

The second phase involved a continued focus on the 3,000-MW load reduction by key users. An additional round of load shedding was implemented in April 2008 to ensure the demand reduction would be sustained. Though load shedding was stopped ahead of schedule on May 1, the savings initiative, per Phase 3, will continue until 2012.

Also in accordance with Phase 3, Eskom is considering additional cogeneration opportunities, which are expected to provide 1,000 MW of capacity over the next two to three years. In addition to recommissioning the three mothballed plants, Eskom is running its OCGT stations. Though these are peaking plants designed to run optimally at 6% load factor and the cost of running them is high due to fuel prices, Eskom says that they can be run for long periods.

The price of power

Along with its concession that new generation was necessary to meet growing demand, the government also agreed in December 2007 that South Africa’s cheap electricity was unrealistically priced, and that an immediate price increase could drive the reduction in consumption and make the viability of independent power producers and cogeneration options more realistic.

NERSA disagreed with Eskom that tariffs needed to increase by about 53% to offset increased coal purchases and greater-than-expected use of expensive peak-load capacity, however. Along with a price hike in December 2007 of 14.2%, in June this year, the regulator only allowed an additional 13.3% for 2008/2009 — bringing the total increase for the year to 27.5%.

The current price of coal-powered electricity in South Africa stands at about 3.09 cents(USD)/kWh, which still puts South African power among the cheapest in the world. But the "era of very cheap and abundant electricity has come to an end," as former President Mbeki said in his State of the Nation address this February. In spite of widespread protests and strikes by miners and factory workers, NERSA expects that every year until 2011, electricity prices will increase from 20% to 25%.

This is good news for IPPs who, at current rates, are unable to compete with Eskom-produced power, said consultancy group Fieldstone Africa in September, especially since an estimated 20,000 MW will be needed from private producers by 2025 to meet Eskom’s predicted demand and expected supply.

Long-term damage control

Eskom continues to pound out plans for new power stations as per its immense building program. (For a detailed list of projects, see "Under construction in South Africa," a web supplement to this story at www.powermag.com.) According to the utility’s 2008 Annual Report, released in July, since the cabinet’s 2004 decision to reverse its ban on capacity building, Eskom has spent a total of 53 billion rand ($6.49 billion), and it will spend another 46 billion rand ($5.64 billion) next year.

So far, six new transmission substations have been completed, and 638 miles of new lines have been installed. Additionally, a total of 2,582 MW of new power generation capacity is now on-line, with 1,061 MW installed during the 2007/2008 fiscal year.

And there’s much more to come: The Eskom board has approved new generation and other capacity with a total output of 16,304 MW. It anticipates that the projects to provide this power will cost 343 billion rand ($43.1 billion) up to 2013. About 46 billion rand ($5.8 billion) will be spent within the 2008/2009 fiscal year alone.

How Eskom will fund its projects remains an unanswered question, however. To date, the South African national treasury has budgeted 60 billion rand ($7.38 billion) over the next three years to help the utility pay for its five-year expansion program. Eskom, which reaped a profit of 974 million rand ($119.13 million) last year, says it plans to raise the rest of the money from the government, capital markets, and development financiers. According to South African newspaper Business Day, Eskom is already in talks with the World Bank for a loan of up to $1 billion a year over five years — talks it initiated after a ratings downgrade made it difficult to access funding on international markets.

Analysts agree that securing funding will remain one of the most important challenges that Eskom faces as it continues to grapple with the crisis. Until it has access to capital, it may just be that — for all its plans — the utility is whistling in the dark.

—Sonal Patel is POWER’s staff writer.