Do Smart Grid Standards Adequately Address Security Problems?

On a frigid, snowy mid-winter morning, some 350 people jammed a meeting room at Ft. Detrick, Md., the home of the nation’s germ warfare program. What brought them together at 7:30 a.m. was not the threat of biological attacks but manmade bugs and threats of another kind. The word "Stuxnet" was on many minds and lips that morning in Maryland.

The local congressman, Republican Roscoe Bartlett, sponsored the meeting as an opportunity for local high-tech businesses to hear more about cybersecurity and the opportunities available in meeting the external and internal threats to our communications and computer infrastructure, including the nation’s electric transmission grid. Bartlett has been leading a charge in the House of Representatives for a more active and aware government approach to protecting the telecommunications and electric infrastructure. His Maryland district encompasses a technology corridor stretching from the Washington, D.C., suburbs north along I-270 to booming Frederick, now Maryland’s second-largest city, after Baltimore.

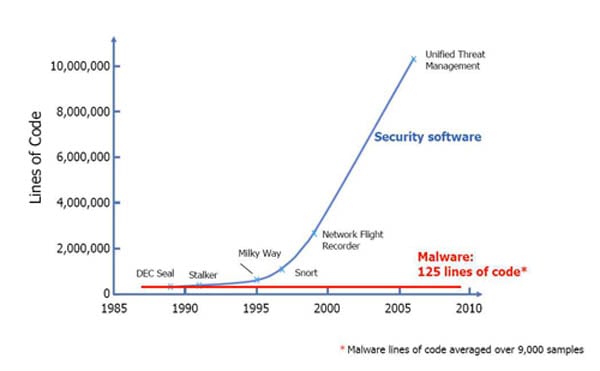

At the meeting, Bartlett displayed a chart produced by the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) showing how unbalanced ("asymmetrical" is the usual buzzword) the cyber threat has become (see the figure). While the complexity of the code that can invade, disrupt, and take control of our cyber infrastructure remains remarkably simple, the software necessary to combat the attacks has grown exponentially complex. According to a DARPA discussion paper on the graphic, "On the defensive side, we move from simple firewalls (earlier) to more complex firewall systems, to today where we have security applications like Symantec with 10 million lines of code. On the offensive side, we see that across 9,000 types of malware, the average has remained around 125 lines of code."

The increase in the number of cyber software threats has exponentially increased the complexity of the security software required to counter the threat. Source: Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA)

"I’m very concerned about the grid," Bartlett told MANAGING POWER. "If we lose the grid for any significant period, people will die. With the smart grid, increased interconnections and communications capabilities introduce new vulnerabilities. There’s not nearly enough attention to grid security."

According to Raj Samani vice president and chief technology officer for McAfee EMEA (Europe, Middle East, and Africa) and EMEA Strategy Advisor at Cloud Security Alliance, security breaches have already struck smart metering technology. In a recent article in ComputerWeekly.com, Samani said that in 2009, a research team found programming errors in smart meter software platforms. The researchers were able to hack into the meters and, from there, reach the system controlling all of the meters. "One meter," he said, "can be used to spread a worm between meters, which could result in a power surge or a shutdown of the grid." Other experts have noted that smart meter technology is now over 10 years old and was not developed with network security in mind.

The Government Accountability Office (GAO) recently found that smart grid cybersecurity guidelines developed by the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) leave major gaps. Also, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) has failed to develop a coordinated approach for monitoring if and how the standards are being followed by industry, and has no way to enforce the standards, according to the congressional watchdog agency.

The GAO’s report, "Electricity Grid Modernization: Progress Being Made on Cybersecurity Guidelines, but Key Challenges Remain to be Addressed," found that NIST "did not address an important element essential to securing smart grid systems that it had planned to include" in its August 2010 first version of smart grid cybersecurity guidelines. The gap, said the GAO, concerns "risk of attacks that use both cyber and physical means." The GAO said, "Until the missing elements are addressed, there is an increased risk that smart grid implementation will not be secure as otherwise possible."

The GAO report also takes an indirect shot at Congress, which set up the process to ensure smart grid security standards in the 2007 Energy Independence and Security Act. "FERC has not developed a coordinated approach to monitor the extent to which industry is following these standards," said the GAO. But the fault, says the report, is in the 2007 law, which "does not provide FERC with specific enforcement authority. This means that standards will remain voluntary unless regulators are able to use other authorities—such as the ability to oversee the rates electricity providers charge large customers—to enforce them." The GAO also notes the Balkanized nature of the U.S. electricity system—"the divided regulation over aspects of the industry between federal, state, and local entities"—which it says "complicates oversight of smart grid interoperability and cybersecurity."

Reps. Bennie Thompson (D-Miss.) and Yvette Clarke (D-N.Y.) asked the GAO to assess the extent to which NIST had developed smart grid standards and evaluate FERC’s approach for adopting and monitoring smart grid cybersecurity. NIST last August issued its first draft of security guidelines for entities such as power companies working on smart grid systems. The Commerce Department agency looked at elements such as an assessment of the cybersecurity risks associated with smart grid systems and the identification of security requirements (that is, controls) essential to securing such systems. "The voluntary standards and guidelines developed through the NIST and FERC processes offer promise," the GAO said. "However, a voluntary approach poses some risks when applied to smart grid investments, particularly given the fragmented nature of regulatory authority over the electricity industry."

Because of the multiple jurisdictions of the U.S. electric system, said the GAO, "state regulatory bodies and other regulators with authority over the distribution system will play a key role in overseeing the extent to which interoperability and cybersecurity standards are followed since many smart grid upgrades will be installed on the distribution system. Such regulatory fragmentation can make it difficult for individual regulators to develop an industry-wide understanding of whether utilities and manufacturers are following voluntary standards."

The GAO report focused on six findings:

- Aspects of the regulatory environment may make it difficult to ensure smart grid systems’ cybersecurity.

- Utilities are focusing on regulatory compliance instead of comprehensive security.

- The electric industry does not have an effective mechanism for sharing information on cybersecurity.

- Consumers are not adequately informed about the benefits, costs, and risks associated with smart grid systems.

- There is a lack of security features being built into certain smart grid systems.

- The electricity industry does not have metrics for evaluating cybersecurity.

The GAO report came just months after the "Stuxnet" worm reportedly infected computers at Iran’s Bushehr nuclear reactor, forcing the country’s secret uranium enrichment centrifuges to shut down. Stuxnet is a sophisticated malware that attacks Siemens’ supervisory control and data acquisition (SCADA) systems. Power plants, factories, and military installations are all vulnerable. The New York Times, citing unnamed military sources, wrote that Israel, with U.S. cooperation, had conducted tests of the destructive worm over two years in a complex in the Negev desert. Both governments have refused to discuss what role, if any, they played in developing or deploying the Stuxnet worm.

—Kennedy Maize is MANAGING POWER’s executive editor. Sonal Patel is a senior writer for POWER magazine.