Coal Plant O&M: How Switching to PRB Lowered O&M Costs

Lansing Board of Water & Light (LBW&L), which has generated electricity since 1892 and steam since 1919 in mid-Michigan, primarily serves the city of Lansing’s business district and all state government buildings in the downtown area. But one of the municipal utility’s plants, Moores Park, has an additional and very important steam customer: General Motors’ Lansing Grand River Cadillac assembly plant. Converting the Moores Park plant to burn Powder River Basin (PRB) coal in late 1999 lowered its O&M costs and eliminated maintenance problems that often could not be fixed without causing lost-time injuries.

Traveler Info

Moores Park has four spreader-stoker boilers that produce 675,000 lb/hr of steam at 275 psi and 650F. Each is equipped with Detroit Stoker grates and coal feeders and a United Conveyor ash-handling system.

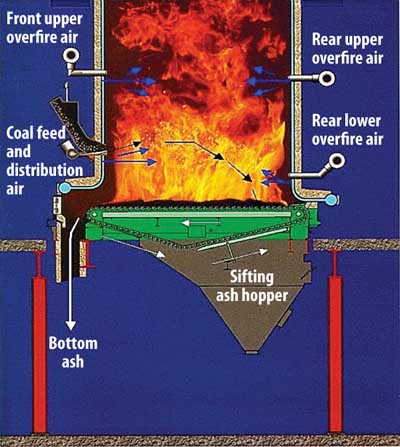

Inside each of the furnace chambers, a moving metal grate moves coal from the rear of the boiler to the front. Feeders at the front push coal into the furnace chamber, where it burns (Figure 1). Combustion air from a forced-draft fan enters the furnace through thousands of holes in the grate.

1. A typical fire at the Moores Park steam plant. Courtesy: Lansing Board of Water & Light

Above the traveling coal bed, any coal not heavy enough (fines) to land on the traveling bed burns in suspension. An overfire air system supplies combustion air from the front and back of the boiler above the traveling grate. Bottom ash drops off the traveling grates at the front of the boiler and is collected in a hopper (Figure 2).

2. Anatomy of a spreader-stoker furnace. Source: Lansing Board of Water & Light

Originally, the spreader-stoker boilers burned an eastern stoker coal that produced 70% bottom ash and 30% flyash. When burning this fuel, loss-on-ignition (LOI) was in the mid-40% range.

Prior to converting to PRB coal, the Moores Park plant had experienced many problems, including:

-

High operator injury rates.

-

High employee turnover, which raised training costs.

-

Boiler emission standards that were difficult to meet.

-

High maintenance costs.

Six to eight operators typically ran Moores Park during the winter — the peak steam generating season, which is when most of the injuries occurred. Most were caused by the handling of flyash and bottom ash. The plant’s flyash hoppers plugged regularly, causing the entrainment of ash in flue gas and the eventual overloading of the plant’s four electrostatic precipitators (ESPs). To fix the problem, maintenance personnel had to manually open and "rod out" the plugged hoppers, putting workers at risk.

The conversion of bottom ash to large clinkers in their own dedicated hoppers was another problem. When Moores Park was running at peak load, it was common to have technicians pulling bottom ash 24/7. Frequent back and hand injuries and skin burns were the result.

Bottom ash was the cause of yet another problem. Because it is abrasive as well as hot, its transport system had to be maintained carefully and repaired frequently at great cost. For example, the four ESPs at Moores Park regularly suffered from downed wires and bridged hoppers. Making matters worse, the overthrow-style feeders of the boilers were expensive to maintain.

Nearby Role Model

In mid-1999, LBW&L executives undertook a project to solve the O&M problems at Moores Park. They began by listing their goals:

-

Reduce employee injuries.

-

Cut plant emissions.

-

Improve production reliability.

-

Improve the combustion process and overall plant efficiency.

As luck would have it, a successful project that shared some of those goals was right next door and suitable for replication. The Moores Park plant shares its building and coal-handling systems with LBW&L’s Eckert power plant, whose six units have a combined capacity of 351 MW. The Eckert plant had just switched to PRB coal earlier the same year. Based on the success of that conversion, and the fuel’s low cost, LBW&L decided to look into converting the Moores Park plant to burn PRB as well.

Eckert’s conversion to PRB coal had transformed it from a plant running two or three units during the week and none on weekends into one that runs all six of its units at full load year-round. Emboldened by Eckert’s notable turnaround, Bob Van Ells — then the manager of electric and steam production at Moores Park — made the decision to switch all four of his units to PRB coal.

Conversion Experience

Just before switching to PRB coal at the end of 1999, and while still burning Kentucky coal, technicians at Moores Park slightly increased the diameter of the holes in the moving metal grates of all four spreader-stokers by one drill-bit size, from ¼ inch to 5/16 inches. Because each grate has 32,000 to 38,000 holes, doing so was a laborious task.

Enlarging the holes dramatically improved combustion in the furnace. As a result, the LOI of flyash dropped from the mid-40% range down to less than 20%, even while still burning eastern coal. After switching to 100% PRB coal, LOI dropped further, settling at 7% to 9%.

Enlarging the grate holes also resulted in:

-

An increase of 50% in the air-to-coal surface ratio.

-

A decrease of air velocity through the ash bed.

-

Elimination of slagging and crusting of ash on the grate.

-

Improved carbon burnout of bottom ash.

In addition to enlarging the holes, modifications were made to increase the overfire air pressure and to reduce the sootblowing frequency. At the same time, the frequency of flyash removal was increased to once per shift and the ash reinjection system air pressure was increased. To achieve complete combustion before the bottom ash drops into the hopper, the grate’s speed was reduced as much as possible.

With the switch to PRB coal, the contribution of bottom ash to total unit ash production was cut by 50% to 60%, so the bulk of the total was now flyash. Because more flyash was now being produced (PRB coal contains more ash than eastern coal), the air pressure of ash reinjection systems had to be increased to keep the systems’ hoppers empty. The extra air also improved combustion of the coal in suspension above the coal bed.

Finally, combustion air dampers located inside the ducting (between the forced-draft fan and the under-grate admission point) were adjusted to optimize the trajectory of air being directed to the grates. Any imbalance caused more air to flow toward the front of the furnace, which, in turn, tended to lift lighter ash up into the flue gas stream.

Moores Park uses an underbunker conveyor system. When the plant switched to PRB coal, the system was upgraded to double its speed. That was necessary to maintain the desired coal feed to meet boiler loads. Because PRB coal has a lower heat content than eastern coal, more of it has to be fed to the boilers to maintain their output.

The Switch Pays Off

Switching to PRB coal has benefitted the Moores Park plant in several ways:

-

In 1999 and 2000, the plant had no lost-time injuries.

-

Boiler emission limits now are consistently achieved.

-

Moores Park now can meet the new Maximum Achievable Control Technology and mercury criteria that went into effect in September 2007.

-

The plant enjoys reduced overtime and operator turnover.

Another benefit is the lower cost of combined coal handling. Because Moores Park and Eckert plants now burn the same fuel, both facilities enjoy lower handling costs. (During the short period in which the two plants burned different coals, coal-handling activities had to be stopped whenever either plant received a delivery.) The cost of Moores Park’s steam production, in dollars per pound, is now less than it was in the early 1990s.

More-reliable steam production and less need for labor-intensive maintenance have helped free up LBW&L’s O&M personnel for other duties. At the Moores Park plant, a seasonal crew of one to four can now do the work that used to require a year-round, five-person crew.

— This item is based on a paper presented by Brian Meaton, operations supervisor, and Bob Van Ells, director of production for LBW&L, at the 2007 PRB Coal Users’ Group meeting.