Australia's Renewables Impasse Weighs Heavily on Generators

The long-drawn-out political impasse on Australia’s review of its Renewable Energy Target (RET) has generators reeling from what they say are “constant policy changes and distortions from successive interference by governments.”

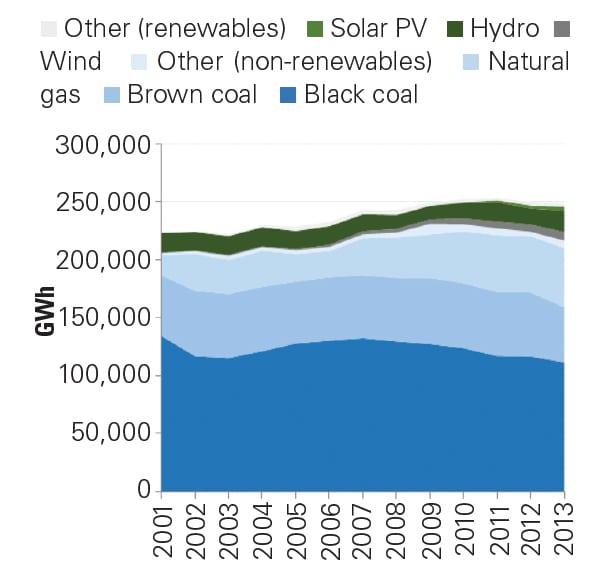

Australia’s RET, which has been in operation since 2001, was increased in 2010 to require that about 20% of the nation’s then-projected demand in 2020 would be met by renewables. The current RET essentially comprises a large-scale renewable energy target (LRET) of 41,000 GWh with contributions from a small-scale renewable energy scheme (SRES) and pre-existing renewables, mostly hydro. However, projected demand for power in the National Electricity Market in 2020 has plunged by about 16% since 2010, which means the LRET now makes up about 27% of projected generation in 2020 (Figure 4).

The coal-rich nation’s energy overhaul began with the election of the current conservative government headed by Prime Minister Tony Abbott. Within a year of the election, Australia became the first nation to abolish a price on carbon, adopting instead the “Direct Action Plan.” That policy mechanism establishes the so-called Emissions Reduction Fund, a pool of capital to incentivize “direct action” by industry to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

Meanwhile, though Abbott had promised not to touch the RET during the election, the government bypassed a 2012 review of the RET by the Climate Change Authority (CCA)—a statutory agency established in 2012 to advise the government on the carbon pricing process—that deemed the RET was stimulating considerable investment in renewable energy and no major changes to it were warranted. Instead, the government commissioned a hand-picked review panel headed by businessman and critic of climate change science Dick Warburton to review the RET and make sure it worked “efficiently and effectively.”

Warburton’s review report released in August 2014 concluded that the cost of the RET essentially outweighed its benefits and that significant change was required. Specifically, it called for the LRET to be either closed to new entrants or for targets to be halved by 2020 to around 27,000 GWh. It also called for the SRES to be either terminated immediately or phased out by 2020 (rather than by 2030, as originally planned). Renewables proponents railed against the findings, saying they represented the “worst case scenario.” The Clean Energy Council, the national trade group, warned that the proposals would “shut down the future of the industry.”

By the start of December, despite several negotiations between the government and the opposition Labor Party, the stalemate over the future of the RET continued. The Energy Supply Association of Australia (ESAA), a self-described “fuel and technology neutral” industry body, warned that Australia’s full electricity generation sector, not just renewable generators, had become “almost unbankable as a result of ongoing policy uncertainty and intervention over the past decade.” It is imperative that major political parties develop a comprehensive national energy strategy for the 21st century, said ESAA Chief Executive Matthew Warren.

“[T]he most conservative estimates suggest the generation industry alone will need to reinvest around [A]$230 billion by 2050 to meet the challenges we face this century,” he said. “It is clearly in the national interest to return confidence to our energy markets and embrace the energy transformation which has already begun. Not because you do or don’t believe in climate change, but because it is a risk that needs to be managed,” he warned.

On Dec. 22, finally, the CCA released a much-anticipated updated review of the RET. But in the document, the CCA admits it had limited time to conduct the review, lamenting at the outset that its own existence faces an “uncertain future.”

Yet, among the CAA’s findings is that, although as currently legislated, the RET arrangements are “not perfect,” they are “effective in reducing emissions at reasonable cost in the centrally important electricity sector.” Moreover, they are “currently the primary policy instruments for electricity sector decarbonisation, and no more cost-effective and scalable measures are in prospect at this time.” Without effective alternative measures, the CCA says it would not favor “significant” scaling back of the 2020 LRET target of 41,000 GWh. However, given the “sharp decline in investor confidence,” the CCA recommends that the government should defer the 2020 target for the LRET by about three years and that the SRES should be left as is.

However, the CCA’s approach hasn’t been palatable to the energy sector. The ESAA almost immediately responded that the review “fails to acknowledge that the scheme as designed is no longer working and that a more strategic review of energy is needed if we are to deliver an efficient reduction in greenhouse gas emissions.” Confidence cannot be restored simply be returning to bipartisan support for the policy as the review suggests, the group said.

“Removing the [carbon] price and expecting the supporting policy to work is like removing the foundations of a house and expecting the walls not to fall over,” Warren cautioned on Dec. 22. “Banks are simply unwilling to invest in any new generation projects of any type for the foreseeable future because chronic oversupply and weak wholesale prices means these investments will only lose money.”

—Sonal Patel, associate editor