Audit Your Coal Dust Prevention Program

The U.S. Chemical Safety Board (CSB), in a November 2006 report, detailed the occurrence of nearly 280 dust fires and explosions in U.S. industrial facilities over the prior 25 years that resulted in approximately 119 deaths and more than 700 injuries. Preparation of the report was motivated by three catastrophic dust explosions in 2003 that killed 14 workers. The CSB subsequently released its "Investigation Report: Combustible Dust Hazard Study" in November 2006; it recommended specific regulatory action by the federal Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) and a change in industry standards, such as the comprehensive standards maintained by the National Fire Protection Association (NFPA).

The CSB report found that the three explosions that occurred in 2003 would have been avoided had the facilities complied with relevant sections of the NFPA standards. The CSB also found that although the NFPA standards are usually incorporated by reference into state and local fire codes, only a few local fire code officials inspected industrial facilities, that those inspections were rare, and that those officials are "often unfamiliar with combustible dust hazards."

A report by OHSA, "Combustible Dust in Industry: Preventing and Mitigating the Effects of Fire and Explosions," describes the cause of a number of industrial dust explosions and useful mitigating actions facilities can employ to reduce the potential for a dust explosion.

Focus on Dust

According to OSHA, "its Combustible Dust National Emphasis Program (NEP) [was begun] on October 18, 2007, to inspect facilities that generate or handle combustible dusts that pose a deflagration/explosion or other fire hazard." Unfortunately, only a year later, another massive sugar dust explosion in Georgia killed 14 workers and injured many more. That February 2008 explosion invigorated OSHA’s Combustible Dust National Emphasis Program. Those 64 industries with a history of dust incidents became the target of increased OSHA inspection visits and, therefore, an increased number of citations were issued.

Beyond the OSHA General Duty Clause Section 5(a)(1) that states an employer is to "furnish to each of his employees employment and a place of employment which are free from recognized hazards that are causing or are likely to cause death or serious physical harm to his employees," a number of other standards and regulations apply.

There are no specific OSHA regulations for handling coal dust for the power generation industry, but a Technical Information Bulletin (TIB 01-11-06), "Potential for Natural Gas and Coal Dust Explosions in Electric Power Generating Facilities," was written "to remind employers who operate electrical power generation facilities about potential explosion hazards."

OSHA issued a directive in February 2008 on the enforcement policy and inspection procedures for "Control of Hazardous Energy (Lockout/Tagout)" and "other related standards." In March 2008, the National Emphasis Program (NEP) for Combustible Dust was reissued.

Power Industry Inspections Decrease

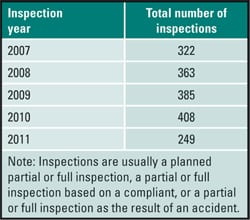

OSHA data seems to indicate very little enforcement activity for fugitive dust in the power industry, as defined by Industry Group 491: Electric Services. The data in the table were extracted from OSHA’s Integrated Management Information System (IMIS), which is available online on the OSHA website to illustrate the number of inspections by OSHA in the power industry.

Total number of OSHA citations for Industry Group 491: Electric Services. Source: OSHA’s Integrated Management Information System

According to the OSHA IMIS, 111 citations were issued to utilities in Industry Group 491 during the period October 2010 through September 2011 (the latest 12-month data available) during only 41 inspections. The total penalties for violations were $593,846. This report lists the cause of the various citations, with what appears to be a small number possibly related to combustible dust.

A related search under the General Duty citation database in IMIS (where OSHA typically writes citations for dust-related violations) found only three citations issued for "Dust & Fumes" issued since January 2007: Two went to a single utility during a visit in 2009 and one in 2010 during another utility visit. The data seems to indicate that there has been little increase in enforcement activity related to coal dust after the NEP for explosion dust began almost four years ago.

Dust Enforcement Up in Other Industries

Nationwide, under all 64 industry SIC codes, the inspection and citation results are quite different. The following paragraphs on the results of the NEP were provided by OSHA and were edited for inclusion in this article.

OSHA has found more than 4,900 violations (3,786 violations of federal standards and 1,140 of state standards) at the facilities inspected pursuant to the Combustible Dust NEP. This includes not only combustible dust-related violations but also violations such as lockout/tagout, walking and working surfaces, and other hazards, through 2009 [the latest data available]. OSHA judges 74% of those violations under federal jurisdiction as "serious," but only 34% of the violations of State Plan inspections are similarly categorized.

Under the NEP, the Hazard Communication standard is the standard most frequently cited with respect to combustible dust-related hazards, followed by the housekeeping standard (Figure 1). OSHA’s housekeeping standard at 29 C.F.R. 1910.22 not only applies to typical housekeeping hazards but also to dust accumulation hazards. In several instances, OSHA found combustible dust accumulations ankle deep and covering an entire room.

1. Number of combustible dust-related violations, all industries, through 2009. Combustible dust citations were about 20% of the total citations issued. Source: OSHA

The average number of violations per NEP inspection is 6.5 in federal enforcement. The total citation penalty amount OSHA has proposed through 2009 (the latest data available) under the Combustible Dust NEP is $14,848,686. However, OSHA proposed the third-largest fine in its history, exceeding $8.7 million, following the Imperial Sugar Refinery explosion in February 2008. The average penalty proposed per serious violation during combustible dust NEP inspections is $1,233 for federal OSHA and $791 for state plans.

Many Citation Categories

Employers were also cited for violations of personal protective equipment, electrical equipment for hazardous (classified) locations, first aid, powered industrial trucks, and fire extinguisher standards during these inspections. OSHA compliance officers even found that compressed air in excess of 30 psi was being used for cleaning purposes. As well as violating an OSHA standard, the use of compressed air to clean accumulated dust would create a dust cloud and can result in deflagration or explosion if ignition sources are present. OSHA issued General Duty Clause citations for this practice.

In the absence of an OSHA standard, OSHA can cite Section 5(a)(1) of the OSH Act, the General Duty Clause, for serious hazards, such as fire and explosion hazards for which there are feasible means of abatement. OSHA has referenced NFPA standards 654, 484, 61, and 664 as potential means of abating combustible dust hazards in citations issued under the NEP. OSHA also referenced NFPA 499 in recommending safe practices for electrical equipment used in Class II locations and NFPA 68 and 69 for explosion prevention and protection techniques. Some of the hazards cited under the General Duty Clause are listed in the next section.

Examples of General Duty Clause Violations

The following list summarizes some of the General Duty Clause citations issued by OSHA under the Combustible Dust NEP. These citations provide excellent "lessons learned" for coal-fired plants, and the problems identified should be addressed when auditing existing coal dust safety programs:

- Dust collectors were located inside buildings without proper explosion protection systems, such as explosion venting or explosion suppression systems.

- Deflagration isolation systems were not provided to prevent deflagration propagation from dust-handling equipment to other parts of the plant.

- The rooms with excessive dust accumulations were not equipped with explosion relief venting distributed over the exterior walls and roofs of the buildings.

- The horizontal surfaces such as beams, ledges, and screw conveyors at elevated surfaces were not minimized to prevent accumulation of dust on surfaces.

- The ductwork for the dust collection system did not maintain a velocity of at least 4,500 ft/min to ensure transport of both coarse and fine particles and to ensure re-entrainment.

- Flexible hoses used for transferring reground plastics were not conductive, bonded, or grounded to minimize generation and accumulation of static electricity. A nonconductive PVC piping was used as ductwork. Ductwork from the dust collection system to other areas of the plant was not constructed of metal.

- All components of the dust collection system were not constructed of noncombustible materials in that cardboard boxes were being used as collection hoppers.

- Equipment such as grinders, shakers, mixers, and ductwork were not maintained to minimize escape of dust into the surrounding work area. Employer did not prevent the escape of dust from the packaging equipment, creating a dust cloud in the work area.

- Interior surfaces where dust accumulations could occur were not designed or constructed to facilitate cleaning and to minimize combustible dust accumulations. Regular cleaning frequencies were not established for walls, floors, and horizontal surfaces such as ducts, pipes, hoods, ledges, beams, etc.

- Compressed air was periodically used to clean up the combustible dust accumulation, in the presence of ignition sources.

- Air from the dust collector was recycled through ductwork back into the work area without the protection of a listed spark detection system, high-speed abort gate, and/or functioning extinguishing system.

- Air displaced during filling and emptying at the packaging and weighing systems that was discharged into the building was cleaned with a filter that was not 99.9% efficient at 10 microns.

- Exhaust ventilation systems were not installed to control dust clouds escaping from blending and other processing machinery.

- Bulk material conveyor belts were not equipped with bearing temperature, belt alignment, and vibration detection monitors at the head and tail pulleys to shut down equipment and/or notify the operator before the initiation of a fire and/or explosion.

- Enclosureless systems were allowed indoors where they were connected to sanders having mechanical feeds; where they were not emptied at least daily; where they were located in areas routinely occupied by personnel; and where they were not separated by at least 20 feet.

- Silos, legs of bucket elevators were not equipped with explosion relief venting.

- Explosion vents on dust collectors and bucket elevators were directed into work areas and not vented to a safe, outside location away from platforms, means of egress, or other potentially occupied areas.

- The dust collector’s baghouse automatic pulse-cleaning system was nonoperational due to equipment defects. The dust collector systems’ hoods and ductwork were in disrepair with substantial air leaks in the ductwork created by missing inspection covers, unused opening, incomplete or poorly designed capture hoods, and physical damage.

- A dust collector collecting aluminum dust was located inside a building and not located outside with appropriate venting and other safeguards to protect employees in the event of an explosion.

- Dust collectors were allowed to be shut down periodically during unloading operations, resulting in the creation of dust clouds in the processing areas. Procedures were not established to shut down related machinery if the dust collection system shuts down.

- Collection points used for manual cleanup of wood dust and other foreign material, including metal, were not provided with magnetic separators, grates, or other types of screening to prevent foreign material from entering into the dust collection system.

- Automatic sprinkler systems were not provided on enclosureless dust collectors operating at 5,500 cfm capacity and were not separated by at least 20 feet from each other when located inside the buildings.

- Process Hazard Analysis was not conducted to determine whether the process hazards necessitated the installation of approved devices such as explosion protection systems, interlocked rotary valves, deflagration vents, and flame front diverters.

- Employees were exposed to explosion hazards due to the nitrogen blanketing piping disengaging from the mixer/blender during the mixing process.

- Mixers and blenders used for the production of pulverized collagen were not dust-tight and not equipped and provided with explosion prevention, relief, and techniques.

- Miter saw was not maintained under continuous suction, thus allowing escape of dust during normal operation.

- The Coalpactors (hammer mills) used to crush coal and their connected feed chutes were not equipped with protective systems to prevent or mitigate a deflagration in the event of an ignition of combustible coal dust inside the Coalpactors.

- The company had not developed and implemented written Management of Change procedures for ensuring that potential changes to production equipment and dust control equipment do not result in fires, deflagrations, and dust explosions.

- Screw conveyors or screw augers were not provided with deflagration isolation devices, such as, but not limited to, deflagration/explosion relief venting, containment, or isolation to prevent continued propagation flame front and overpressure into adjacent building/structures or equipment.

- The employer did not provided adequate maintenance and design of dust collector systems, creating insufficient air aspirations, low duct velocities, and blocked ducts.

- Propane burners with open flames were used in the area where agricultural products were ground.

- Employees were using electric grinder(s) on a duct entering a baghouse-style dust collector without a hot work permit system.

—Dr. Robert Peltier, PE, is COAL POWER’s editor-in-chief.