Algeria, like other countries that are members of the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), wants to diversify its electricity production, and is looking to solar power for the bulk of its new generation capacity. About 98% of Algeria’s electricity today comes from natural gas, but analysts have said the North Africa country’s high sun radiation level makes it one of the largest markets for solar power on the continent.

“Algeria should attempt to reduce its dependence on natural gas for electricity,” said Rym Loucif, an Algiers-based partner with the French law firm LPA-CGR avocats. Loucif told POWER, “The development of renewable energies represents an essential vector for the sustainable economic and human development of the country.”

|

|

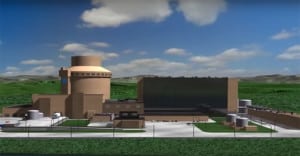

1. Solar power experts have said the Tafouk 1 project in Algeria could at least partly resemble the Noor Complex solar farm, near Ouarzazate in Morocco, on the edge of the Sahara Desert. The Noor project, shown here, was built in three phases, and has a total generation capacity of 580 MW. Courtesy: ECOHZ |

Algeria, with a population of 44 million, has set a goal of producing at least 22 GW of power from renewable resources by 2030, including at least 13.6 GW from photovoltaic (PV) solar. The country’s current installed solar generation capacity is just 343 MW. Algerian officials in late May said they plan to launch the Tafouk 1 project (Figure 1), which would consist of several solar power plants with combined generation capacity of about 4 GW. The office of Prime Minister Abdelaziz Djerrad said following a May 21 government meeting, “In addition to meeting national demand for energy and preserving our fossil resources, this project would allow us to position ourselves on the international market.”

Cecily Davis, the co-head of the Africa Group for European law firm Fieldfisher, told POWER that Algeria’s funding of renewable energy projects likely will be impacted by the decline of the oil and gas industry. “One of the obvious points to make is how unfortunate it is, [Algeria’s] reliance on oil and gas,” said Davis, who works out of Fieldfisher’s London office. “One of the concerns is how to fund this energy infrastructure, since one of the ways to do that is through taxes on oil and gas.”

Mohamed Arkab, the country’s minister of energy, in a May 20 videoconference said the project could cost as much as 390 billion Algerian dinars ($3.6 billion). Arkab said the country hopes to have the project online in 2024. Arkab in a presentation said the solar farms would be sited across a dozen wilayas, or provinces, in Algeria, encompassing an area of nearly 16,000 acres. He said the project would create about 56,000 jobs during construction, with about 2,000 workers needed to operate the plants.

“A lot of countries are seeing [renewable energy] as job creation,” said Davis. “It’s about how you transition a population, and give them new skills. Algeria may be an attractive jurisdiction to be investing in solar.”

Loucif told POWER that “the Algerian government has expressed its willingness to promote the realization of the Tafouk 1 project by attracting foreign investors,” with Loucif noting the renewable energy sector “is not subject to the so-called 51/49 rule,” in which foreign investment in Algerian projects has been capped at 49%. “In other words, renewable/solar energy are now open to foreign investment without any obligation to enter into a partnership with a local party.”

Arkab said the project would allow Algeria to start “exporting electricity at a competitive price, as well as exporting the know-how we have acquired.” Exports of hydrocarbons—oil and gas—represent about 95% of Algeria’s foreign currency earnings, and the sector accounts for more than half of the country’s gross domestic product. Paul Stockley, who helps lead Fieldfisher’s oil and gas practice from London, told POWER, “There’s the oil price challenge, with revenues on the decline. If you overlap that with the whole energy transition piece, and you overlay that with COVID-19, there’s a real rationale for doing [renewable energy projects].”

Algerian officials in early May, prior to announcing the Tafouk 1 project, said they would cut the country’s budget by half for the remainder of 2020, due to declining revenues from the oil sector. Officials earlier this year said Algeria would seek foreign loans in 2020 for the first time in years, with Loucif noting the government is sending “a strong positive signal to international companies and developers of its intention to attract them through a business-friendly legal system.”

Said Stockley: “You have to look at the investment appetite of investors to go into Algeria. There are countries that have a better investment climate. There are security concerns [in Algeria], and concerns about fiscal terms, and the bureaucracy. My sense is that Algeria as a country recognizes it needs to sort this out. The new hydrocarbons law makes [the country] more fiscally attractive, and time will tell whether it attracts new investment.”

Algeria’s new hydrocarbon law, enacted at the start of this year, is designed to reverse declining foreign upstream investment through improved contract terms and tax rates. Officials said the law is essential for restoring the attractiveness of investment in the energy sector, particularly as competition increases among countries that want new investors, in particular foreign investment.

“The [government] also intends to give priority to the use of external financing to fund solar projects, in particular from international financial institutions [IFIs], as recalled by the government when it voted the Finance Law for 2020 in December 2019,” said Loucif. “The IFIs play in particular a role to accelerate the development of renewable energy projects, and to promote their funding.”

“Algeria is not one of the countries [with a lot of foreign investors],” said Davis. “We don’t see projects coming up there very often. If we look at jurisdictions that have a lot more traction, there’s a lot going on in Uganda, in Kenya, Ethiopia, obviously stuff going on in West Africa. [Algeria] isn’t a country that we see that investors are especially attracted to… I’m curious myself as to how much traction it will get with foreign investors,” with new fiscal regulations in place.

The Algerian Electricity & Gas Regulation Commission last year issued a tender for 150 MW of solar power, but only eight of the 93 prequalified bidders were shortlisted, with a procurement of only 50 MW. That award went to Condor, an Algerian solar module manufacturer, which led a consortium that plans a 50-MW plant in the Biskra region. The project’s power purchase agreement set its price at 6.9 cents/kWh.

Oil and gas companies that have operated in Algeria, including the country’s own Sonatrach, along with Italy’s Eni and France’s Total, have signed contracts for solar power projects, though development has been slow. Eni and Sonatrach jointly built a 10-MW solar plant in 2017, and have said they will expand their joint solar ventures, with plans to build arrays at oil and gas production sites. Sonatrach’s 2030 Vision plan calls for the installation of 1.3 GW of solar generation capacity at the company’s oil and gas sites, and it says solar power could “cover 80% of our [power] needs on site.”

Davis and Stockley both said having large institutional investors, such as the World Bank, become active in the country would go a long way toward helping Algeria meet its ambitious goals for renewable power, including for Tafouk 1. “In terms of the financing of solar PV, and the scale of this ambition, there’s a big challenge around whether [this] project, and the country as a whole,” can find the needed funding, said Stockley. Davis noted, “Rightly or wrongly, people get a sense that it’s an acceptable project if there’s World Bank involvement, or other large institution. [Algeria] still suffers from lots of unpleasant headlines and nervousness. The World Bank brings credibility.” The World Bank since 2010 has had a strategic partnership framework with Algeria, known as Reimbursable Advisory Services (RAS), which the World Bank said are offered in response to requests for support with development priorities.

Loucif agreed that having international banks on board with project development is key for countries such as Algeria. “The IFIs [International Finance Corp., African Development Bank, French AFD, etc.] generally provide states and developers of renewable energy projects with suitable financing structures (mixing loans and grants) on attractive terms,” she said. “To accelerate the development of projects, the country will have to make an effort to adapt, simplify, and speed up the granting of licenses, authorizations and permits by public authorities. Here the collaboration with IFIs could be very helpful for the country. For example, IFC’s Scaling Solar Program is a ‘one stop shop’ program [combining financing and regulatory auditing] aimed to make privately funded grid-connected solar projects operational within two years and at competitive tariffs.”

—Darrell Proctor is associate editor for POWER (@DarrellProctor1, @POWERmagazine).