A Winning Combination: Government and Utilities Partner on Renewable Energy Projects

Recent mandates require government facilities to develop energy policies that enable energy conservation, increase the use of renewable energy, and improve energy security. Utilities with government facilities in their service territory may have opportunities to develop solar and other renewable energy projects that help them meet state renewable portfolio standards while increasing a government facility’s usage of renewable energy. The key to such a win-win proposition is careful structuring of the project agreement to leverage each party’s assets.

Many electric utilities in the U.S. face mandates to increase their percentage of electricity generated from renewable resources. However, many have struggled to develop renewable energy projects that provide electricity at a cost comparable to that of fossil-fueled generation.

Government facilities are subject to similar mandates to reduce fossil fuel consumption and increase the use of renewable energy to reduce adverse environmental impacts and to increase energy security. They too have struggled to meet their mandates in a cost-effective manner due to a lack of funding, inability to take advantage of federal tax credits, and lack of expertise in developing electricity generation assets.

Carefully structured agreements between utilities and government facilities can result in synergistic relationships that enable both parties to satisfy their renewable energy mandates. This article explores agreement structures related to solar projects, but the basic structure may be applicable to other renewable energy sources.

Why Utilities Are Pursuing Renewables

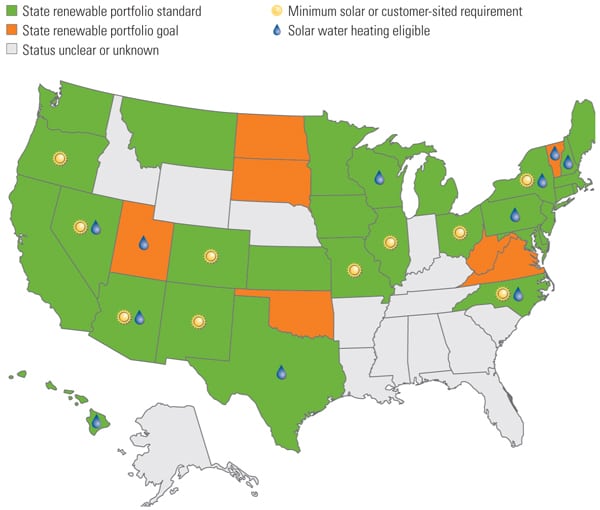

As of 2010, 29 states, plus the District of Columbia and Puerto Rico, have adopted renewable portfolio standards (RPS), which require electric utilities to produce a certain percentage of their total generation with renewable resources (see Figure 1 and the table).

|

| 1. States with renewable portfolio standards. As of September 2010, 29 states, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico had developed RPS policies. Seven had set goals. Data are as of October 2010. Source: Database of State Incentives for Renewable Energy (DSIRE) |

|

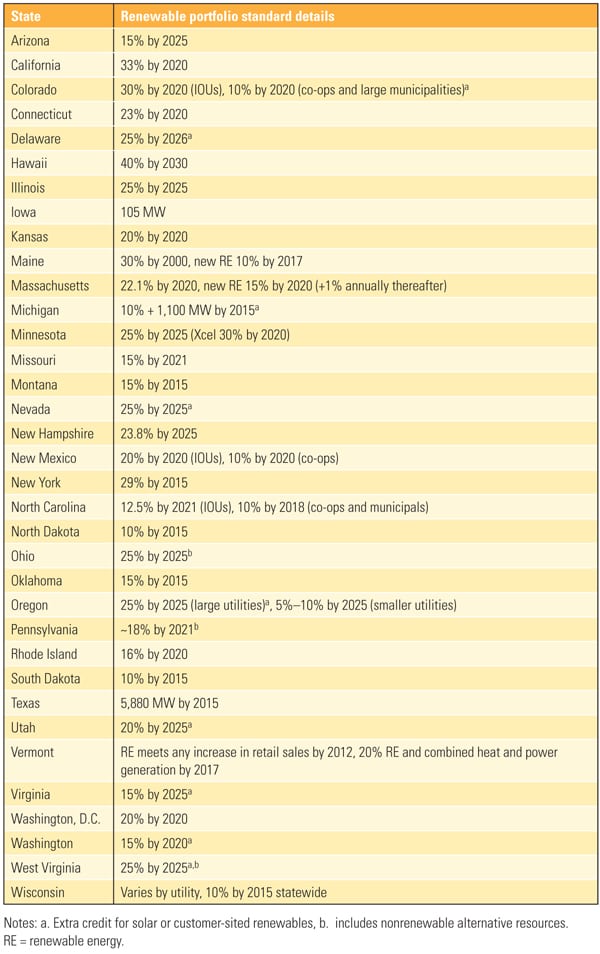

| Details of state renewable portfolio standards. Source: DSIRE |

Investor-owned utilities (IOUs) failing to meet mandates face fines for noncompliance. For example, California will assess fines of 5 cents per kWh for every kWh that a utility falls short of sourcing from renewables, up to a maximum penalty of $25 million, according to the California Public Utilities Commission, Decision 03-06-071, R.04-04-026.

Additionally, regulatory uncertainly related to implementation of a cap-and-trade system or carbon tax has caused many utilities to focus their development efforts on renewable energy projects until a federal policy is adopted.

Government Drivers Are Important

U.S. policy increasingly addresses our dependence on finite resources and resources that produce carbon emissions. The U.S. Department of Energy’s (DOE’s) Federal Energy Management Program (FEMP) facilitates the federal government’s implementation of sound, cost-effective energy management and investment practices that address this dependence and enhance the nation’s energy security and environmental stewardship. As part of the energy management strategy, recent laws and executive orders direct federal agencies to increase their use of such renewable energy sources as solar and wind power.

The Energy Policy Act of 2005 (EPAct) and its implementing guidance direct that, to the extent economically feasible and technically practicable, 3% of the electrical energy consumed by federal agencies in fiscal years 2007 through 2009 come from renewable energy. This percentage gradually increases to 7.5% annually beginning in fiscal year 2013. In addition, proposed legislation, Senate Bill 1321, would increase these goals to 10% by FY 2010 and 15% by FY 2015. It is likely that this provision will be reintroduced in energy legislation in the next Congress.

The Energy Independence and Security Act (EISA) of 2007 focused on reducing energy consumption and promoting sustainable design. Section 433 of EISA directs the DOE to issue revised federal building energy-efficiency performance standards within one year of its enactment. The revised standards specify that “buildings shall be designed so that the fossil fuel–generated energy consumption of the buildings is reduced, as compared with such energy consumption by a similar building in fiscal year 2003” (as measured by Commercial Buildings Energy Consumption Survey or Residential Energy Consumption Survey data from the Energy Information Agency), by the following percentages: 55% by 2010, 65% by 2015, 80% by 2020, 90% by 2025 and 100% by 2030. In addition to the direction given to increase energy efficiency and decrease overall energy consumption, incorporating renewable resources will be essential to achieving these goals.

In addition, Executive Order 13423 directs that, in each fiscal year, an amount of renewable energy equal to at least half of the statutorily required renewable energy that is consumed by a federal agency must come from new renewable sources placed into service after Jan. 1, 1999.

The U.S. Department of Defense (DOD) has been directed to increase renewable energy use beyond what is required of other federal agencies. Section 2911(e) of Title 10 U.S. Code establishes a goal for the DOD “to produce or procure” not less than 25% of its total facility electricity consumption during fiscal year 2025, and each fiscal year thereafter, from renewable energy sources. The National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) of 2007 codifies the DOD’s voluntary goal of 25% and extends the 25% renewables requirement to all “electric energy” consumed by 2025 (Section 2853 (e) (1).

Many Synergies Exist

Renewable energy mandates could be the catalyst for utilities and government facilities to develop synergistic partnerships that leverage land, tax circumstances, and capital.

Land. Utilities often face a daunting task in obtaining public utility commission approval for renewable energy projects due to the relatively high cost of renewable energy—and the resulting impact on ratepayers—compared to traditional generation resources. Furthermore, a unique characteristic of utility-scale solar installations is the large land mass required. Solar installations have a low energy density compared with fossil-fueled plants: approximately 5 to 7 acres per MW of installed capacity. Because of the large land requirements, any time utilities can minimize the costs of land acquisition and associated development, the overall capital cost of a solar project can be significantly reduced.

As it happens, government facilities often have an abundance of land that may be suitable for the development of large solar installations.

Capital. A government facility may have land but may lack direct access to the capital required to construct solar facilities within its annual budget. At the facility level, personnel may not be aware that capital funds are available for renewable projects, and if they are aware, the application process can be cumbersome and time-consuming.

Taxes. Because federal and state agencies do not pay federal taxes, they are not able to take advantage of federal tax incentives. Therefore, renewable energy projects commissioned by state and federal agencies can effectively cost up to 30% more than private-sector installations. This makes it difficult for government facilities to demonstrate payback periods or returns on investment typical of private sector installations. However, federal tax incentives significantly improve the project economics for solar and other renewable energy projects in the private sector.

Combining Forces. To make the most of these different dynamics, the DOD has funded renewable energy initiatives at its installations using both upfront appropriated dollars and various agreements with private-sector entities, under alternative financing approaches. In recent reports, the DOD has recognized that upfront appropriated funding is effective in developing smaller renewable energy initiatives. However, upfront appropriated funding may be a poor fit for developing the larger, higher-cost renewable initiatives that are necessary to achieve established renewable energy goals. This scenario makes the DOD more receptive to alternative financing and partnership arrangements with utilities, because:

- Larger utilities typically have access to capital (or the ability to rate-base capital projects), the opportunity to take advantage of tax breaks, and large-scale development experience.

- Leveraging a utility’s capital and tax advantages with a government facility’s land may result in a cost-effective project satisfying the renewable energy mandates for both parties.

An IOU Contracting Approach

Utilities working with a government facility that has land suitable for solar development may be able to leverage their capital to install a solar system on that land (Figure 2).

|

| 2. Power purchase agreement between an investor-owned utility and government entity. Investor-owned utilities may find that they can work cooperatively with a government agency or military facility to facilitate construction of a solar power project on government land using utility capital. Source: DSIRE |

A typical contract between a utility and a government facility would contain the following provisions:

- Government facility provides land to the utility for a renewable energy project. This agreement may be structured in the form of a lease, with monthly payments, or an easement.

- The utility leverages its capital to construct the solar generation system.

- The utility recoups its capital investment from the government facility via monthly energy payments for delivered energy. However, as a concession for the use of the land, the power purchase agreement (PPA) may fix the electricity rate throughout the duration of the PPA or fix the annual escalation to a relatively small percentage. The utility may accept this risk, as the escalation need only account for inflation but need not account for (nonexistent) fuel cost increases, which typically account for the majority of escalation risk.

- Renewable energy certificates (RECs) generated by the solar installation would be retired by the utility for compliance with the state RPS.

- The utility would typically be responsible for ongoing operation and maintenance of the solar installation.

This contract structure provides a number of important benefits to the utility, such as:

- Compliance with RPS mandates while minimizing impact to other ratepayers.

- Reducing the need for additional fossil-fuel peaking generation assets in regions with afternoon load peaks because of the similarity of those load profiles and the generation profile of a solar power plant located in the Southwest.

- Allowing utilities to maintain customer load—and therefore revenue—because the generation is on the utility side of the meter instead of on the customer’s side, as it might be with new rooftop solar generation on the government facility.

- Qualifying the utility for the federal Investment Tax Credit (ITC). The ITC provides a substantial tax benefit for the utility. The utility is also able to take advantage of accelerated depreciation provisions allowed for solar installations.

This contract structure also provides benefits for the government facility:

- Compliance with renewable energy mandates.

- Potential long-term cost savings and protection from electricity rate escalation via fixed energy rates or contractually fixed escalation rates.

- A contract structure allowing the government facility the benefit of reduced renewable energy costs obtained (indirectly) through the ITC.

- On-site generation that improves energy security for the facility because, in the event of a renewable system outage, the facility can continue to be supplied by the utility’s existing distribution system.

Municipal/Co-op Contracting Approach

Developing PPAs between public power utilities and government facilities that deliver similar benefits presents additional challenges because municipal utilities and cooperatives typically do not pay federal income taxes and, therefore, cannot take advantage of the ITC. Furthermore, some municipal utilities and co-ops may not have sufficient capital to fund construction of a large solar facility. If it is allowed in the state, adding a third party to the PPA can result in a synergistic relationship similar to that achieved by the IOU approach (Figures 3 and 4).

|

| 3. States allowing third-party solar power purchase agreements (PPAs). At least 17 states and Puerto Rico allow third-party PPAs. Data are as of July 2010. Source: DSIRE |

|

| 4. A PPA between a public utility and a government entity incorporating a third-party investor. Because municipalities and public electric cooperatives do not pay taxes, financing a solar project may be difficult. A third-party investor can use tax incentives and renewable energy credits to finance the project, making a PPA a feasible route to implementing a solar generation facility on a government entity’s land. Source: DSIRE |

A typical contract between a municipal utility or co-op, a government facility, and a third-party financier would include terms such as these:

- The government facility provides land for a solar installation via a lease or an easement.

- The third party leverages capital to construct the solar power installation and qualify it for the ITC, resulting in a substantial tax benefit, effectively reducing the capital outlay.

- The third party maintains ownership of the solar facility, allowing that party to take advantage of the accelerated depreciation.

- The third party and municipal utility or co-op establish a PPA in which the third party sells renewable energy to the utility. With input from the government facility, the utility negotiates a long-rate structure for the renewable energy for the duration of the PPA.

- The municipal utility or co-op sells renewable energy to the government facility under an existing service contract using its existing distribution system.

- If the state RPS applies to municipal utilities and co-ops, the RECs generated by the facility would be retired by the utility for compliance with the state RPS. If the state RPS does not apply to municipal utilities and co-ops, the RECs could be held by the third party and sold to improve project economics.

- A buyout provision may be included in the PPA allowing the utility to purchase the solar facility at fair market value after the third party has fully depreciated the asset.

- The utility would typically be responsible for ongoing operation and maintenance of the solar installation.

In this contract structure, the government receives the same benefits listed earlier. This contract structure also provides attractive benefits to the municipal utility or co-op, including these:

- Compliance with RPS mandates (if applicable to municipal utilities or co-ops in the state).

- Reduce the need for additional fossil-fuel peaking generation assets in regions with afternoon load peaks because of the similarity of those load profiles with the generation profile of a solar power plant located in the Southwest.

- Maintained customer load and, therefore, revenue.

The third party, assuming it has earnings to offset with tax credits, also has an attractive list of benefits:

- Leverages capital to secure tax savings via the ITC.

- Qualifies for additional tax savings via accelerated depreciation.

- Leverages capital to produce a higher rate of return than other investments, presuming a well-executed project.

- Minimizes long-term operational risk exposure through the ability of the utility to purchase the solar facility (if a buyout provision is included).

DOD Project Implementation

The service branches of the DOD are developing strategies to achieve the results required under the various energy policy directives. For example, the Army is actively implementing projects to satisfy congressional, administration, and DOD mandates and directives. The Army expects to meet the stricter definitions of EPAct 2005 on its way to meeting the higher renewable energy goals of the NDAA 2007. It is working to satisfy multiple organizational goals and constraints while securing its energy supplies and focusing on procurement of the lowest-cost energy that meets high reliability standards and minimum vulnerability to interruption from natural or intentional causes, thereby increasing security.

In recent years, the Air Force has led the charge in renewable energy. According to the DOE’s Energy Information Administration, the Air Force has been the top federal purchaser of renewable power for several years. In 2006 it purchased more renewable energy than any other entity in the U.S. The Air Force is the third-largest renewable energy purchaser nationally, according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

The Air Force also continues to be at the forefront in adopting alternative financing and partnership arrangements with renewable energy producers. It is beginning to use 20-year enhanced use lease arrangements (EULs) to provide land for solar arrays. These EULs have historically been used to bring retail outlets or private industry to military bases and are commonly accepted under federal procurement regulation.

The Army National Guard, Air National Guard, and Navy are also rapidly developing and implementing procedures and standards that follow the DOD’s guidelines.

— Matthew Brinkman, PE ([email protected]) is the solar business unit manager for Burns & McDonnell’s Energy Group. Tanya Martella, MA, LEED AP ([email protected]) is a client manager for Burns & McDonnell’s aviation and facilities group.